The British Royal Family can trace their lineage right back to Cerdic of Wessex (519-534), founder and first king of Saxon Wessex, which is not bad for a family tree. As with all royal families, they inter-married with other European Royals over the years, and many fought and died to retain the English crown (merged with the Scottish crown on the ascent to the throne in 1603 of James VI of Scotland as James I of England). Significant events leading to the present royal family include William the Conqueror (who had an excellent claim to the British throne) being the first to be crowned in London’s Westminster Abbey in 1066, nearly 1000 years ago, then the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660 after the British decided they regretted beheading Charles I and the intervening dictatorship of Oliver Cromwell, and the avoidance of various Roman Catholic monarchs, unpopular in a largely Protestant nation.

The stories of the last twelve British monarchs together tell us how our present King, Charles III, is able to unite the nation with the joy of a coronation while he and his family perform public functions like opening new public buildings rather than ruling like an elected Prime Minister. King Charles remains the ultimate guardian of ‘fair play’ in the British Constitution, just like his predecessors for hundreds of years.

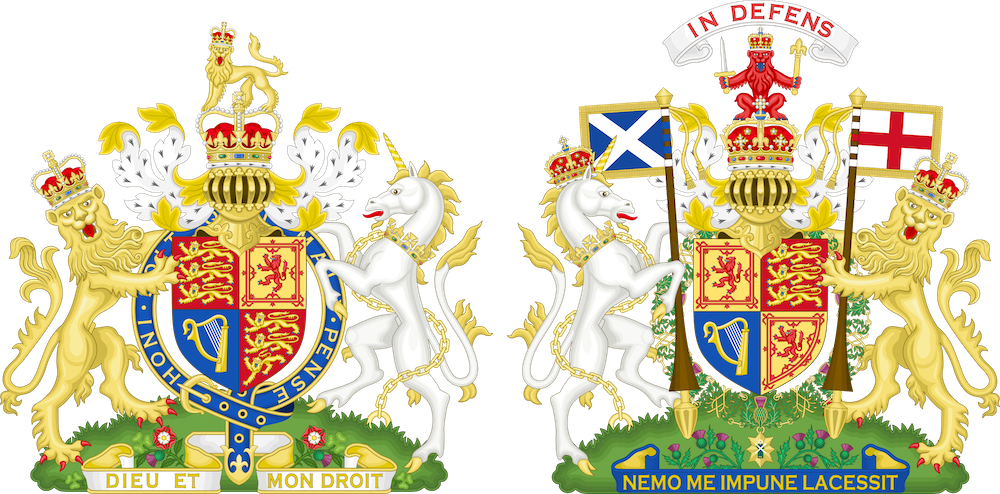

British Royal coat of arms – the common version on the left; the Scottish version on the right. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

British Royal coat of arms – the common version on the left; the Scottish version on the right. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

British Monarchs: The last Stuart

1702 – 1714: Queen Anne

Poor Queen Anne had 17 pregnancies, but only one child survived – and he died of smallpox aged 11. She is currently most famous from the 2018 film ‘The Favourite’ where she is played by Olivia Colman and portrayed as a lesbian. The three leading actors in it all won a bucket-load of awards, and Colman scooped the Oscar for best actress. The gist of the film is indeed true, namely that Anne had a close best friend, Sarah Churchill (ancestor of Winston Churchill) and wife of heroic General John Churchill, and Sarah was slowly replaced in Anne’s affections by the much poorer Abigail Masham. Britain certainly prospered during Anne’s reign, and London’s magnificent St Paul’s Cathedral was completed. Unlike Anne’s father James II, who had to flee after just three years on the throne as he was a Roman Catholic, Anne and her sister Mary (Queen between Anne and James) were themselves Protestant. Anne’s unfortunate lack of children meant that the crown passed over the heads of her many Roman Catholic relations to her distant Protestant cousin George, the Elector of Hanover.

British Monarchs: Queen Anne, painted by Willem Wissing and Jan van der Vaardt. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

British Monarchs: Queen Anne, painted by Willem Wissing and Jan van der Vaardt. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

British Monarchs: The Hanoverians

1714 -1727: King George I (George Louis)

George I was really not a happy bunny as British king. In his native Hanover, he held real power, while in England, he had to deal with Parliament and Prime Ministers. This was not helped as George barely spoke a word of English. He only became king because King James I of England (who was also James VI of Scotland) was his great-grandfather, but the many other possible heirs to the throne were Roman Catholic, so they were not offered the British crown. George arrived in Britain aged 54 with 18 cooks and two ‘mistresses,’ one of whom became known in the British court as ‘the Elephant’ and the other as the ’Maypole.’ His two mistresses played cards with him on alternate nights. George had had his wife imprisoned for thirty years, and he started the Hanoverian tradition of not getting on with his son. In 1720, George was implicated in the South Sea Bubble, a massive financial scandal of grossly over-priced shares.

British Monarchs: King George I painted by Sir Godfrey Kneller. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

British Monarchs: King George I painted by Sir Godfrey Kneller. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

1727 – 1760: King George II (George Augustus)

Though happier speaking English than his dad, George I, the British Prime Minister Sir Robert Walpole firmly continued to run the country under George II – not least through cleverly allying with George II’s wife, Queen Caroline. In 1734 George II’s proud boast to Caroline was ‘Madam there are 50,000 men slain this year in Europe and not one Englishman.’ In 1743, George was the last English king to lead an army into battle (at Dettingen, in modern Germany). The ‘rightful’ heirs to the British throne, the Roman Catholic Stuart family, launched their final attempt to regain the throne in 1745. The Stuart claimant, known as ‘Bonne Prince Charlie,’ landed in Scotland and marched his army as far south as Derby but tactically (and, arguably, fatally) turned them back when there was a run on the pound in London. Bonnie Prince Charlie escaped to France and died a drunkard in Rome. George’s son Frederick predeceased him, so George II’s grandson became George III.

British Monarchs: King George II painting by Thomas Hudson, 1744. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

British Monarchs: King George II painting by Thomas Hudson, 1744. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

1760 – 1820: King George III (George William Frederick)

Sadly, George III has gone down in recent history as ‘Mad King George’ after the extremely successful British film ‘The Madness of King George’ (1994). He was the grandson of George II, which is why he reigned for so long and was the first English-speaking monarch since Queen Anne. Though his reign began reasonably well, he did indeed suffer from a mental illness due to intermittent porphyria and eventually became both blind and insane. While limited free speech meant the British Prime Minister Charles Fox felt able to call his King ‘a blockhead’, on the other side of the Channel, the French were at this time taking their kings to the guillotine.

On the negative side of George’s reign, the 1773 the ‘Boston Tea Party’ led to the American colonies proclaiming their independence on 4th July 1776. On the plus side, due to the heroic behaviour of sailors like Horatio Nelson and generals like the Duke of Wellington, Britain stood virtually alone against the might of Napoleon and the spirit behind the French Revolution, and the development of Britain’s burgeoning Empire continued. George’s son (late George IV) ruled as Prince Regent after 1811 until George’s death.

British Monarchs: King George III coronation painting by Allan Ramsay, 1762. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

British Monarchs: King George III coronation painting by Allan Ramsay, 1762. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

1820 – 1830: King George IV (George Augustus Frederick)

The coronations of Charles III and his mother, Elizabeth II, owe more to George IV than anyone else. Known as ‘Gorgeous George’ for his taste in expensive clothes – and expensive everything else, George revelled in pomp and ceremony, and his splendid coronation was the apotheosis of his life. He so detested his wife, Caroline of Brunswick, that he ensured she was kept out of his opulent coronation, banging on the doors of Westminster Abbey. While Prince Regent, George created the popular Regents Park and the Brighton Pavilion, and his love of architecture meant he was able, as King, to ensure Windsor Castle was lavishly refurbished. He also transformed Buckingham House (later Buckingham Palace) for the royal family. In his private life, he kept mistresses and his expensive tastes, and his love of banqueting meant he became massively obese and, towards the end, his poor health rendered him almost immobile. On his death, the London Times wrote, ‘Never was an individual less regretted than this deceased king.’

British Monarchs: King George IV coronation portrait by Thomas Lawrence, 1821. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

British Monarchs: King George IV coronation portrait by Thomas Lawrence, 1821. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

1830 – 1837: King William IV (William Henry)

In great contrast to his brother, George IV, the young Prince William had done a real job – he had served in the Royal Navy. Aged 64, when he ascended to the throne, William hated the pomp of monarchy and wanted to dispense with the Coronation altogether! After his brother’s excesses, his lack of pretension of itself meant he became very popular. During his brief reign, Britain modernised its values, perhaps helping to ensure there was no anti-royal revolution in Britain. Parliament abolished slavery in the colonies in 1833 (slave-owners rather than slaves received compensation), and (after much rioting) middle-class men with property won themselves the vote. William had ten children with his long-standing mistress Dorothea Jordan but left no male heir.

British Monarchs: King William IV portrait by Martin Archer Shee, 1833. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

British Monarchs: King William IV portrait by Martin Archer Shee, 1833. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

1837 – 1901: Queen Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria)

Queen Victoria was a granddaughter of George III by his fourth son. Just 18, when she inherited the throne, she was very much under the wing of Prime Ministers early on in her reign. She had nine children, 40 grandchildren, and 37 great-grandchildren – her descendants are many of Europe’s current monarchs. In 1840, she married her cousin Albert of Saxe-Coburg, who she passionately loved. Albert brought the German

idea of the Christmas tree with him to Britain and had tremendous influence over the sometimes headstrong Queen. When he died in 1861, she withdrew from public life for some years and was forever dressed in black, much to public displeasure.

Victoria was jealous that though the British had the largest empire the world had ever known (it doubled in size during her reign), she was not an Empress like the ruler of Austria-Hungary. One of her Prime Ministers, Benjamin Disraeli, who was brilliant at ‘playing’ the experienced Queen (she was by then far more difficult to manipulate than she had been at the age of 18) sorted this by having Victoria declared ‘Empress of India’ in 1876.

By 1887 she had recovered from the death of her darling Albert enough to lead her Golden Jubilee, and in 1897 the British Empire throughout the world was able to celebrate their somewhat aged queen’s Diamond Jubilee. A century later, in 1997, the movie ‘Mrs. Brown’ was released, portraying the rumours the Queen (played by Judi Dench) was too close to a Scottish manservant John Brown. She later became close to an Indian, Abdul Karim, who was her teacher or ‘Munshi.’ This did not go down well, either, with her advisers. ‘The Munshi occupied very much the same position as John Brown used to do,’ her equerry wrote in a letter, though Victoria dismissed their complaints as racial prejudice.

British Monarchs: Queen Victoria painting by Franz Xaver Winterhalter, 1843. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

British Monarchs: Queen Victoria painting by Franz Xaver Winterhalter, 1843. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

British Monarchs: House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (Named after Prince Albert)

1901 – 1910: King Edward VII (Albert Edward)

Edward VII finally succeeded his mother to the throne at the age of 59 after his mother’s long life. In his youth, Edward’s irresponsible behaviour was a matter of such concern to his parents that Queen Victoria did not allow him even to see state papers. He reminded her of the much unloved George IV. Though Edward indeed loved horse racing, gambling, and women (Camilla, Charles III’s Queen Consort, is the great grand-daughter of one of Edward’s mistresses, Alice Keppel), Edward proved himself a capable king during a time of great change. Creaks were by now beginning to show in Britain’s economic power, not just from the US industrial strength, but Edward’s first two cars were a Mercedes and then a Renault!

Edward’s funeral is described by one historian as ‘the greatest assemblage of royalty and rank ever gathered in one place, and, of its kind, the last.’

Queen Monarchs: King Edward VII by Sir (Samuel) Luke Fildes. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Queen Monarchs: King Edward VII by Sir (Samuel) Luke Fildes. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The House of Windsor 1910 – the present

The name of the royal family was changed from ‘Saxe-Coburg and Gotha’ in 1917, during the first World War, as a heavy aircraft, named the Gotha G.IV, could be seen bombing London directly, and Gotha became a household name. Windsor is simply the name of the small town where the Royal Family lives in Windsor Castle.

1910 – 1936: King George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert)

George V had not expected to be king during his youth, but when his elder brother died aged just 28, George realised he would then have to step up on the death of their father, Edward VII. In 1893 George married Princess Mary of Teck, his dead brother’s fiancée. It was not simply the horrors and death of the First World War that made his reign traumatic. His cousins, the Russian Royal family (the Romanovs, who

he knew quite well) appealed to him for asylum in Britain after the Russian Revolution, but he felt unable to offer it. They were lined up and shot in 1918 (it is said George V could never forgive himself for this in later life). Though usually a conservative, he said of the many trade unionists joining the General Strike against the Conservative Government in 1926, ‘try living on their wages before you judge them.’

In 1932 George began the tradition of the royal Christmas Day broadcast (which later proved such a problem for his stuttering son when he became king). Towards the end of his reign, George and his wife were (rightly!) much concerned by their eldest son, Edward the Prince of Wales, and Edward’s infatuation with the divorcée, Mrs. Wallis Simpson. In the year before he died, George said of his son Edward, ‘After I am dead, the boy will ruin himself within 12 months.’ Of his second son Albert (later George VI) and his grand-daughter ‘Lilibet’ (later Queen Elizabeth II we all respect so dearly), the king said, ‘I pray to God my eldest son will never marry and have children, and that nothing will come between Bertie and Lilibet and the throne.’

George V and his doctors had hoped that an ultimately unsuccessful visit to Bognor on the British south coast would improve his ailing health, leading many to speculate that the King of England’s last words were ‘b*gger Bognor.’

British Monarchs: King George V painting by Luke Fildes. Photo Credit: © Public Domains via Wikimedia Commons.

British Monarchs: King George V painting by Luke Fildes. Photo Credit: © Public Domains via Wikimedia Commons.

1936: King Edward VIII (Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David)

Edward VIII abdicated (resigned) in December 1936 before his coronation. He was the most popular Prince of Wales Britain has ever had. As a single man, he was the most photographed celebrity of his time and was particularly popular on his trips around the Commonwealth and North America. Consequently, when Edward renounced the throne to marry Mrs. Wallis Simpson, the British found it almost impossible to believe, as, until early in December 1936 (unlike people outside the UK), the British people knew nothing about Mrs. Simpson. Wallis Simpson was an American, a divorcee, and had two living ex-husbands. Unsurprisingly, this was unacceptable to the Church of England, of which Edward, as king, would be head, following the tradition set by Henry VIII back in the 1530s. Edward married Wallis Simpson, and they went to live in Paris as Duke and Duchess of Windsor. Edward was never to return to public favour not least because, in 1937, one of the first things they did after abdication was to go to Nazi Germany and meet and greet Hitler. Perhaps foreseeing current poor fraternal royal relations, his brother King George VI described Edward’s decision to visit Germany as ‘a bombshell, and a bad one.’

British Monarchs: King Edward VIII, when he was Prince Wales. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

British Monarchs: King Edward VIII, when he was Prince Wales. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

1936 – 1952: King George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George)

George was a shy and nervous man with a stutter (made famous in the film ‘The King’s Speech’), very much in contrast to his brother Edward VIII. The prestige of the throne was low when George became king, but his wife Elizabeth (later known as the ‘Queen Mother’ till her death in 2002), and his own mother, Queen Mary, were exceptional in their support of him. The Second World War started in 1939, and the royal couple became symbols of resistance, especially when photographed viewing bomb damage to their home, Buckingham Palace. It was bombed more than once in the war, but it was where they lived for the duration of the war. (Some had wanted to move the royal couple to Canada.)

Meanwhile, the King’s daughters, the future Queen Elizabeth and her sister Margaret spent their war years at Windsor Castle. King George successfully dissuaded his Wartime Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, from landing with the troops in Normandy on D-Day. The post-war years of his reign were ones of great social change and saw the start of the British National Health Service. George was also the last Emperor of

India from 1936 until the British Raj was dissolved in August 1947 and then the first Head of the Commonwealth from 1949. His great tragedy was dying at the young age of just 57.

British Monarchs: King George VI painting by Gerald Kelly. Photo Credit: © Public Domains via Wikimedia Commons.

British Monarchs: King George VI painting by Gerald Kelly. Photo Credit: © Public Domains via Wikimedia Commons.

1952 – 2022: Queen Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary)

Elizabeth, or ‘Lilibet’ to her close family, must surely have lived one of the most bizarre lives of the twentieth century. She was born in a not especially sumptuous or ‘royal-looking’ flat in Central London in April 1926. Elizabeth was the niece of the heir to the throne, so extremely unlikely ever to be Queen. After her uncle abdicated, she became heir, and she was only in her mid-twenties when a holiday in Kenya was interrupted by the news that her father, George VI, had died at a young age and she was the Queen of the British Empire (or, by then, the Commonwealth). At her coronation in 1953 (the first one to be televised), there were Britain’s Dukes in their finery and their coronets, Prime Ministers and Presidents from British ‘dominions’ all over the world there to recognise the young Elizabeth as their Queen.

Fast forward forty-five years to 1997, Britain was no longer a great power, Africa had been ‘lost,’ the Queen’s family secrets were regularly spread all over newspapers (including tapes of her son Charles’s intimate phone calls to his lover). Many in the country felt that her response to the death of Princess Diana, her son’s estranged wife, showed she was out of touch. It was deemed appropriate that she should share a cup of tea in a ‘Council House’ (government housing for people on lower incomes).

Elizabeth’s strengths were many. During the Second World War, she trained as a driver and mechanic. She married her cousin Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, and they had four children: Charles (now Charles III), Anne, Andrew, and Edward, so there were heirs a-plenty. On 9th September 2015, Elizabeth became Britain’s longest-serving monarch and died at Balmoral in Scotland on 8th September 2022

at the age of 96. Her jubilees, from the Silver Jubilee in 1977 to her Platinum Jubilee in June 2022, were moments of great national celebration.

In an era where popular politicians and stars can easily be spurned for their unfortunate ‘gaffes,’ Elizabeth’s ability never to put a foot wrong (the main requirement of a monarch) in 70 years must surely be one of the factors that makes her probably the greatest of the last dozen British monarchs.

Coronation portrait of Queen Elizabeth II, June 1953, London, England. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Coronation portrait of Queen Elizabeth II, June 1953, London, England. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

2022 – present: King Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George)

Following the death of Queen Elizabeth II, Charles succeeded to the throne at the age of 73, taking the title King Charles III, and his wife Camilla became Queen Consort. Charles is the oldest heir apparent to succeed to the British throne. Before becoming King, he was perhaps known most dramatically for his divorce from his much-loved first wife, Princess Diana. As someone with both a military background, an academic background (he has a Cambridge degree), and a successful head of many businesses and charities throughout his long preparation to be king, he may be the ‘most qualified to be King’ the nation has yet known.

King Charles II at the Palace of Westminster. Photo Credit: © House of Lords 2022 / Photography by Annabel Moeller via Wikimedia Commons.

King Charles II at the Palace of Westminster. Photo Credit: © House of Lords 2022 / Photography by Annabel Moeller via Wikimedia Commons.

One of the most exciting aspects of visiting London is knowing that so many of its amazing buildings (Westminster Abbey, Buckingham Palace, Windsor Castle, and so on) that professional guides can show you around, remain working buildings to this day. They are still linked to their current role in this unique, majestic, long-lasting royal family, that on one level may be a simple story like a television soap opera, but on another level, the monarchy is what defines and binds the United Kingdom as a historic nation.

Leave a Reply