The Tower of London is one of the most popular sites in our capital city, attracting more than 2.8 million visitors a year. One of the main draws is the Jewel House, located in the heart of the Tower grounds. It contains some of the most precious gems you’re ever likely to see: the royal ceremonial regalia known as the Crown Jewels.

In peak months, there’s a very good chance you’ll spot Blue Badge Tourist Guides leading their clients to the Jewel House as early as possible. This is to avoid the queue that is sure to build later in the day, full of people eager to see the priceless wonders that have been kept at the Tower for safekeeping for centuries.

The Crown Jewels are the most spectacular and complete collection of royal regalia in the world, and some of the pieces have been used in every coronation since 1661. Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II had her coronation in 1953 and is now the longest-reigning monarch in British history. But not all of the Crown Jewels have been sitting idle since then. This is still very much a working collection. In fact, on the special occasions when one of the items leaves the Tower, you’re likely to find a sign in its display case, saying “In Use.”

Tower of London – Entrance to the Jewel House and signage. Photo credit: © Historic Royal Palaces.

Tower of London – Entrance to the Jewel House and signage. Photo credit: © Historic Royal Palaces.

The Imperial State Crown

Boasting an incredible 2,868 diamonds, the Imperial State Crown is worn by the Queen at the annual State Opening of Parliament – the ceremony marking the start of the new parliamentary year. At least that was the case until October 2019, when the Queen chose to wear the George IV Diadem (familiar to those who still buy postage stamps). The Imperial State Crown, at 2lbs (907g), is sadly now too heavy for a woman in her 90s. Instead, it sat beside her on a cushion – a tradition usually reserved for State Openings where a new monarch has acceded to the throne but not yet had their coronation.

The crown is so important that it rides in its own carriage – along with the Sword of State (see below) and the Cap of Maintenance (a symbol of the sovereign’s authority) – in the procession ahead of the Irish State Coach that carries the queen!

The Imperial State Crown features pearls said to have belonged to the first Queen Elizabeth (who died in 1603), and other incredible precious stones. These include the second-biggest clear-cut diamond in the world, the Cullinan II, with 317.4 carats. The biggest is also in the Jewel House. The Cullinan I, or First Star of Africa, has a staggering 530.2 carats. It sits atop the Sovereign’s Sceptre with Cross. In its original rough form, the Cullinan diamond was sent to London from South Africa in a plain box by normal post, while a replica was transported by ship as a decoy.

Other stones on the crown include the Black Prince’s Ruby, (in fact a spinel, a semi-precious stone), which first adorned the crown in 1685. It was said to have been given to the Black Prince – son of King Edward III – by the King of Castille in the 14th century. On the crown’s other side is the Stuart Sapphire, a most beautiful blue stone, acquired by George IV from a grandchild of James II, though at George IV’s own coronation in 1821 it adorned the “ample arm” of his mistress, Lady Conyngham.

Prince Philip & Queen Elizabeth II wearing the Imperial State Crown after Coronation. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Prince Philip & Queen Elizabeth II wearing the Imperial State Crown after Coronation. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Sword of State

A sword has been carried ahead of the monarch during processions since at least the 9th century.

Charles II hastily commissioned a Sword of State after he returned from exile to take back the throne during the 1660 Restoration of the Monarchy. In those days, the sword was used so frequently – for example, on the way to church and to Parliament – that another was commissioned in 1678. This is the one that you see on show at the Tower, the original having disappeared.

The sword is adorned with intricate foliage, with a lion and a unicorn at the end of each handle. The scabbard is actually made from wood and covered in velvet and silver-gilt mounts.

Along with the Imperial State Crown, the Sword of State takes pride of place in Queen Alexandra’s State Coach in the procession to the State Opening of Parliament. It is then carried, point up, ahead of the Queen as she makes her way to her throne in the House of Lords.

It was also used for the investiture of the Prince of Wales at Caernarvon in 1969 and at the VE Day Service at St Paul’s Cathedral in 1995.

British Coronation Swords: The Sword of Offering, the Sword of State, and the Sword of Mercy. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

British Coronation Swords: The Sword of Offering, the Sword of State, and the Sword of Mercy. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Lily Font

The beautiful Lily Font was commissioned by Queen Victoria in anticipation of the birth of her first child. It’s one of only two English silver-gilded fonts (the other being the font that sits nearby in the Jewel House, made for Charles II in 1660).

The Lily Font has a border of water lilies and leaves with three cherubs at the base. Lilies are said to represent purity, while water lilies are associated with new life.

It was used at the christenings of all of the Queen’s grandchildren except for Princess Eugenie (younger daughter of Prince Andrew). She was baptised in the parish church in Sandringham, and the policy at that time was that the Lily font didn’t leave London. However, this rule was relaxed, and when Princess Charlotte (daughter of Prince William) was baptised in the same church, the font was taken there for the occasion.

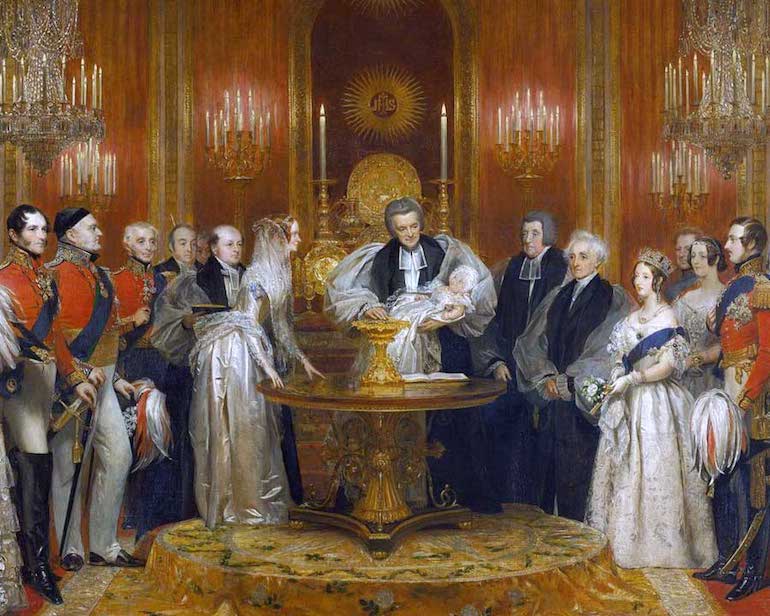

Painting by Charles Robert Leslie of The Lily Font at the christening of Victoria, Princess Royal, 10 February 1841. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Painting by Charles Robert Leslie of The Lily Font at the christening of Victoria, Princess Royal, 10 February 1841. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Maces

There are ten maces on show at the Tower of London, which date back to the late 17th century and were made for Charles II, James II, and William and Mary. Maces have evolved from being medieval battle axes, carried by bodyguards.

A further three are on permanent loan to the Houses of Parliament. Two of these represent the monarch’s authority and are carried in and out of the Chambers in procession at the beginning and end of each day. In the House of Lords, the Mace is placed behind the Lord Speaker on the Woolsack. In the House of Commons, it’s placed on brackets on the table in front of the Speaker.

Neither House can meet or pass legislation without a mace present. This ritual was tested in 2019, when in a moment of frustration during a Brexit debate, Lloyd Russell-Moyle, MP, grabbed the mace from the middle of the Commons Chamber and started to walk out. Amid shouts from MPs including “Expel him!” and “Disgrace!”, the Speaker demanded its immediate return.

The third mace accompanies the Lord Chancellor on official duties outside the House of Lords.

Top of one of the British ceremonial maces bearing the cypher of Charles II. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Top of one of the British ceremonial maces bearing the cypher of Charles II. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Maundy Dish

Compared to some of the beautifully decorated plates and dishes in the Jewel House, the Maundy Dish is relatively plain. The centre is engraved with the coat of arms of William III and his wife, Mary II.

The dish is removed from the Tower and used in the Maundy Service on Maundy Thursday (the day before Good Friday). From the Middle Ages to the late 17th century, English monarchs washed the feet of paupers on Maundy Thursday, in imitation of Christ’s act of humility and love for his disciples. The washing of the feet ceased in 1685, but the distribution of alms continues, with the purses carried on the Maundy Dish.

The Queen introduced the custom of travelling to a different city each year for the service, and the number of gifts contributed corresponds to her age at that time. So in 2020, 94 men and women will receive gifts in recognition of their contribution to their community and to the church. Each person gets a red and a white purse. The red contains a small amount of ordinary coinage to symbolise the Sovereign’s gift for food and clothing (in 2019 this was a special £5 coin to commemorate the 200th anniversary of Queen Victoria’s birth), and the white contains Maundy coins to the value of the Sovereign’s age. These are legal tender, though people prefer to keep them for posterity.

Given the number of purses that need to be distributed now, two altar dishes are used to supplement the Maundy Dish.

So next time you visit the Jewel House with your Blue Badge Tourist Guide, if you spot a piece missing behind the glass, you’ll know where it might be!

Leave a Reply