Did you know that the word museum means a “Temple to the Muses”, all of whom were female? The British Museum in London is a museum of world history, but all too often that history has ignored half of the world. This is true even though women have wielded power in a variety of ways. In ancient Greece, Aristotle believed it was the natural order of things for women to be subordinate to men, that men were more virtuous, brave and intelligent. He also believed that men’s blood was hotter than women’s blood! Well, on both counts, he was wrong of course. Many influential women not only overcame existing barriers of gender inequality but also proved that women can be as strong, brave and influential as men. Sometimes even more so. A tour of the British Museum with a Blue Badge Tourist Guide can provide much evidence of this fact and might include some of the following displays about ground-breaking women:

NOOR INAYAT KHAN

Young Noor Inayat Khan did not have an ordinary life. She was a descendant of Tipu Sultan, the famous 18th-century ruler of Mysore in India, and daughter of Hazrat Inayat Khan, who came from a princely Indian Muslim family. She became an SOE (Special Operations Executive) agent during the Second World War. She was the first female radio operator to be sent by Britain to France and worked as a secret spy there, helping the French resistance against the Nazis. Khan displayed exceptional courage. However, she was betrayed on 13 October 1943, arrested and interrogated by the Germans. On the morning of 13 September 1944, Khan was executed. She was 30 years old. Learn more about her extraordinary sacrifice in the Sir Joseph Hotung Gallery, where her George Cross medal for bravery, awarded posthumously, is displayed.

British Museum in London: Noor Inayat Khan, bronze by Karen Newman. Photo Credit: © Ingrid M Wallenborg.

British Museum in London: Noor Inayat Khan, bronze by Karen Newman. Photo Credit: © Ingrid M Wallenborg.

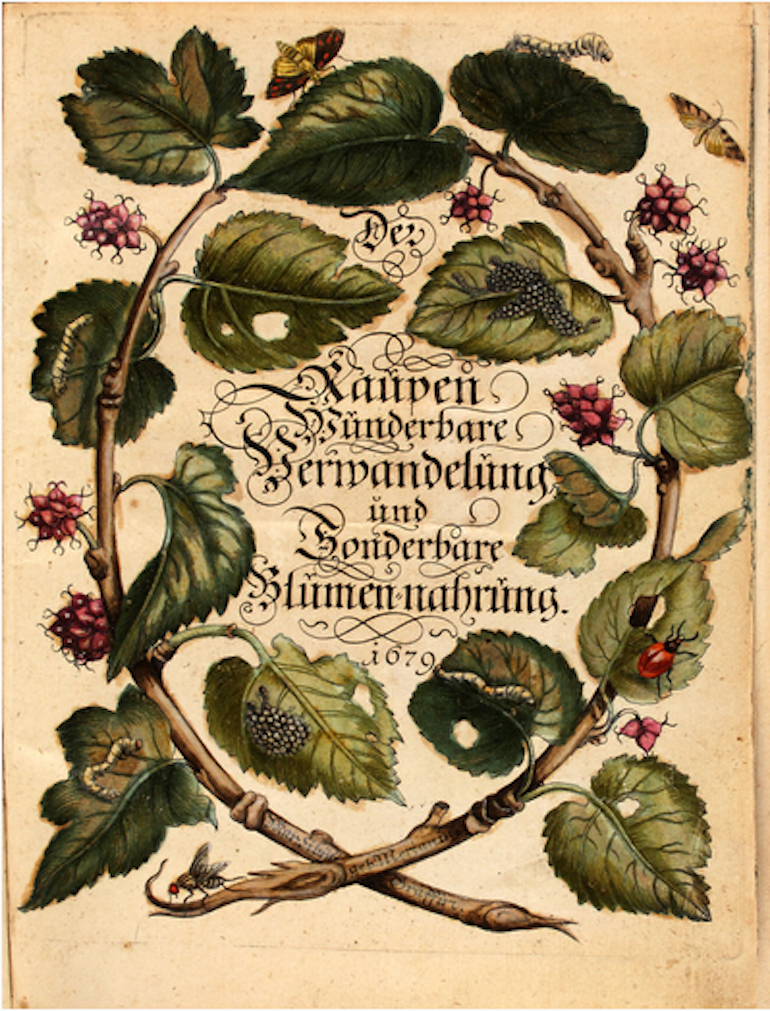

MARIA SIBYLLA MERIAN

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717) started to collect insects and raise silkworms at the age of 13. She would go on to become a trailblazing naturalist and artist. Born in Frankfurt am Main, she was one of the first naturalists to study insects. Her classification of butterflies and moths is still used today. She undertook scientific expeditions at a time when these were still very unusual and the preserve of men. In 1699, while in her early 50s, she travelled to Suriname in search of insects. The 7,500-km voyage took about two months. The detailed pictures she made of animals and plants found there were ground-breaking and are amongst her best-known illustrations. Let your Blue Badge Tourist Guide show you one of her albums displayed at the British Museum and reveal more about her life and that of other exceptional women scientists, including Mary Anning, the palaeontologist.

Title page of The Caterpillars’ Marvelous Transformation and Strange Floral Food, the first volume, published 1679 by Maria Sibylla Merian. Photo Credit: © Wikimedia Commons.

Title page of The Caterpillars’ Marvelous Transformation and Strange Floral Food, the first volume, published 1679 by Maria Sibylla Merian. Photo Credit: © Wikimedia Commons.

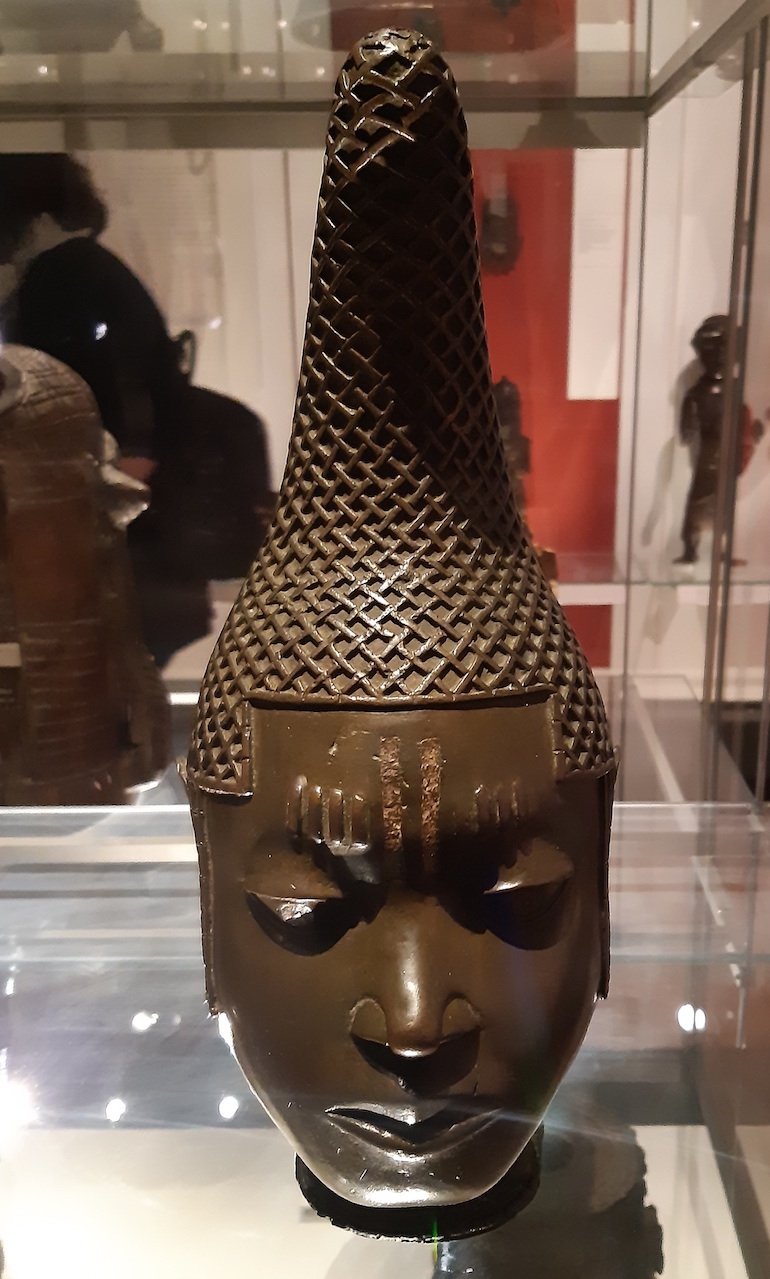

QUEEN IDIA

Queen Idia, also known as the first Queen Mother of Benin, is still remembered in Nigeria today as “the only woman who went to war”. As the 15th-century wife of the oba (king) of the ancient African kingdom of Benin in today’s Nigeria, she gave birth to a son, the future Oba Esigie. Like all good mothers, she backed her son and used her influence to assist him, even raising an army to help him fight powerful enemies. Her son honoured her by creating the unique title of Iyoba (Queen Mother), and the many brass and bronze heads cast in her memory bear witness to her fame. She has remained an inspirational role model for subsequent queen mothers and all mothers in the kingdom. The beauty and striking naturalism of the early cast of Queen Idia displayed in the Africa gallery makes it exceptional. She is also credited with inventing a new hairstyle, known as a parrot’s beak, clearly visible on the British Museum head.

Bronze head of Queen Idia at the British Museum in London. Photo Credit: © Jononmac46 via Wikimedia Commons.

Bronze head of Queen Idia at the British Museum in London. Photo Credit: © Jononmac46 via Wikimedia Commons.

SAINT AGNES

One of the most precious objects in the Medieval Gallery is the Royal Gold Cup, made in France in the late 14th century. The scenes represented, in great detail and glowing enamel, depict the dramatic life story of Saint Agnes. Hardly a dull moment in her life you might say! The daughter of a wealthy Roman at the time of Emperor Constantine, she had the temerity to refuse the advances of Procopius, the son of a high official, who appears to have been stalking her. As punishment, she was condemned to life in a brothel and then attacked by her spurned suitor, who in turn was strangled by a demon, represented on the cup looking quite evil. Eventually, Agnes was condemned to burn, but initially, the flames had no effect. And so the drama continues. St Agnes is now venerated in the Roman Catholic Church and is the patron saint of young girls. Find out more about her martyrdom, what happened afterwards, and the famous owners of this remarkable cup on a guided tour.

British Museum in London: St Agnes, the Royal Gold Cup, 14th C, France. Photo Credit: © Ingrid M Wallenborg.

British Museum in London: St Agnes, the Royal Gold Cup, 14th C, France. Photo Credit: © Ingrid M Wallenborg.

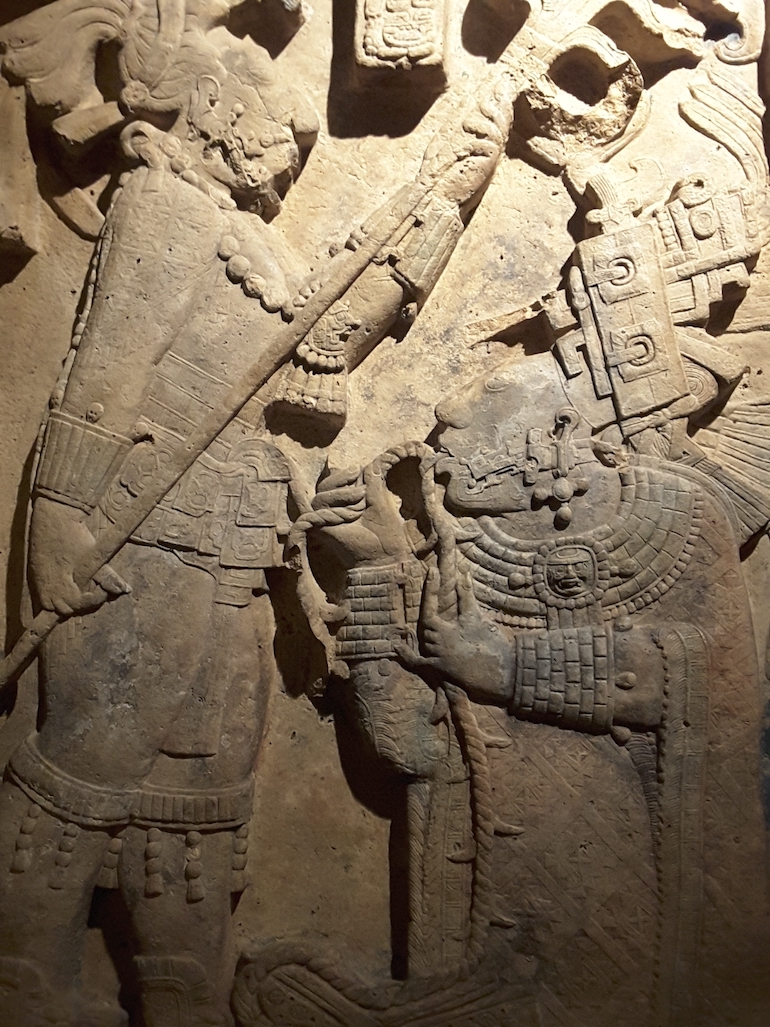

LADY XOC

In the Mexican gallery, you will find a series of unique 8th-century stone lintels from the Maya culture. One of them represents King Shield Jaguar II and his wife, Lady Xoc. The couple are engaged in a rather gruesome bloodletting rite. A kneeling Lady Xoc pulls a rope studded with what are probably obsidian blades through her tongue, while blood falls into a bowl on the ground. She undertakes this painful ordeal in order to contact Shield Jaguar’s spiritual ancestors. For the queen to inflict such severe pain on herself was an extraordinary act of piety. Bloodletting was an ancient tradition of the Maya, and it marked all the main points of their life, notably the path to royal power. What is unusual here is that the principal role in the ritual is carried out by a woman; indeed Lady Xoc is considered to be one of the most powerful women of the Maya civilisation.

British Museum in London: Lady Xoc, from Yaxchilan, Mexico 8th C. Photo Credit: © Ingrid M Wallenborg.

British Museum in London: Lady Xoc, from Yaxchilan, Mexico 8th C. Photo Credit: © Ingrid M Wallenborg.

GREEK RUNNING GIRL

In a room full of Greek vases, a small bronze statue from the 6th century BC – possibly from Sparta – shows a running girl. She wears a tunic covering only her left shoulder and breast, extending down to just above the knees. She turns her upper body, looking back as she dashes forward. The ancient Olympic Games in honour of the god Zeus, which inspired the modern games, are well-known, but only men were allowed to compete during antiquity. However, there was also a lesser-known festival honouring the goddess Hera (wife of Zeus), which included foot races for unmarried girls. What little we know of this festival, the Heraia comes from Pausanias, a 2nd-century AD Greek traveller. He described the girls’ attire for the games: They wore their hair down their back and a tunic hanging almost as low as the knees, covering only the left shoulder and breast. Just like the British Museum running girl! The first woman Olympic champion recorded was Cynisca, a wealthy Spartan princess who won the four-horse chariot races in 396 BC and 392 BC. Since she couldn’t race herself, she hired men to do so on her behalf, but then wasn’t even allowed to watch her own victories. Cynisca is recognised as a pioneer for women taking an active part in the Olympic Games in ancient Greece.

British Museum in London: Greek Running Girl, 6th Century BC. Photo Credit: © Ingrid M Wallenborg.

British Museum in London: Greek Running Girl, 6th Century BC. Photo Credit: © Ingrid M Wallenborg.

PENTHESILEA

The daughter of the god Ares and Otrera, Royal Gold Cup is an Amazonian queen from Greek mythology. In the legendary Trojan War, she assisted the Trojans, who were fighting the Greeks. She demonstrated fierce dedication as a warrior but was eventually killed by Achilles, the Greek hero. Achilles then mourned her, falling in love with Penthesilea because of her beauty and bravery. This very moment is captured on a 6th-century BC amphora displayed in one of the Greek galleries, and it was represented in text and imagery across classical Greece. There were many warrior women in the ancient world. Although most scholars maintain that Amazons were fictional, recent archaeological investigations in Armenia suggest that there really was a band of fierce women fitting the description. In the British Museum, you can also marvel at the fighting skills of these forceful women on the frieze of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, where they are giving the Greeks as good as they get!

British Museum in London: The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, c 350 B.C. modern Bodrum, Turkey. Photo Credit: © Ingrid M Wallenborg.

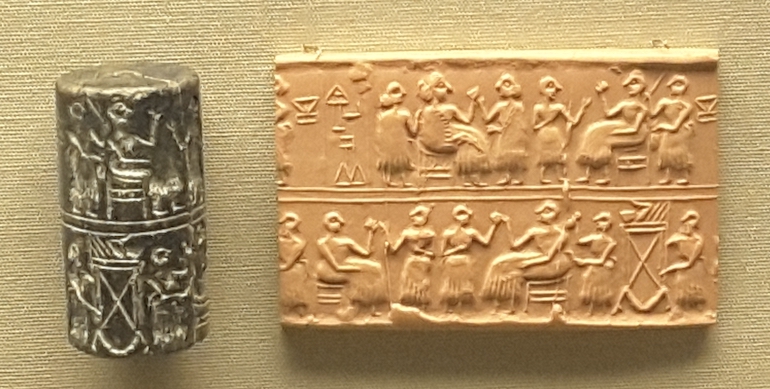

PUABI

In early Mesopotamia, during the 3rd millennium BC, even women of high status were generally described only in relation to their husbands. The fact that Puabi is identified without mention of a husband may suggest she was queen in her own right. Her name and title are known from an inscription on a cylinder seal found on her person in her grave at Ur in today’s Iraq. Today you can see the seal and also her amazing jewellery, once buried with her in her tomb, displayed at the British Museum. This includes items of gold and lapis lazuli. Puabi wore chokers, necklaces, large earrings, and ten rings on her fingers. The discovery of her tomb was part of a major excavation in the 1920s and 1930s, which also greatly inspired a famous female crime writer. Find out more from your specialist Blue Badge Tourist Guide!

British Museum in London: Seal and seal impression from the grave of Puabi from Ur, Mesopotamia, c 2600 BC. Photo Credit: © Ingrid M Wallenborg.

British Museum in London: Seal and seal impression from the grave of Puabi from Ur, Mesopotamia, c 2600 BC. Photo Credit: © Ingrid M Wallenborg.

I end by quoting Dame Mary Beard, professor of Classics at Cambridge University:

“We have no template for what a powerful woman looks like, except that she looks rather like a man.”

“Women in power are seen as breaking down barriers, or alternatively as taking something to which they are not quite entitled.”

Leave a Reply