The once-marshy neighbourhood of Bankside was previously a military garrison within the City of London limits. Museum of London archaeologists discovered Roman warehouses here during the development of the Jubilee Line. The Norsemen were here too. King Alfred’s battling with the Vikings gives us the nursery rhyme ‘London Bridge is falling down.’

Bankside, referred to by some as the ‘Tijuana of Medieval England’, was put on the map conspicuously in the eleventh century as the ‘Liberty of the Clink’. The Bishops of Winchester inherited the lands via Archbishop Odo, brother to William the Conqueror. The bishops ruled the place as a type of libertarian free zone, sandwiched between the buttoned-up City of London and the respectable county of Surrey. Here the usual standards of decorum did not apply.

Bankside became the home of London’s seventeenth-century theatres, taverns, and brothels. This working-class district went on, in the nineteenth century, to be the centre for smelly industries like tanneries, brewing, and vinegar making – all safely downwind of posh Westminster and noble St James’s. Its history is as chaotic as it was colourful. Bankside has experienced insurrection, fire, and violence first-hand, including the 1381 Peasants’ Revolt and the 1780 anti-Catholic Gordon riots, so vividly recounted by Charles Dickens.

Commit No Nuisance sign along Bankside in London. Photo Credit: © Antony Robbins aka Mr. Londoner.

Commit No Nuisance sign along Bankside in London. Photo Credit: © Antony Robbins aka Mr. Londoner.

Crime and immorality

Bankside was a place of outsiders. And against this permissive and chaotic backdrop of opportunity, immorality, and crime, a lively sex trade flourished and catered for all tastes. Sex workers operated in the so-called stews, dominated by giant fishponds used to feed the local populace. The Bishops of Winchester lived off the earnings of these local prostitutes, who were known as Winchester Geese. Their name may derive from the beckoning gestures they made to punters, with an extended arm and hand resembling the neck and beak of a goose. Our innocent expression about getting ‘goosebumps’ has darker origins – to be ‘bitten by a goose’ meant acquiring a sexually-transmitted disease!

The Winchester Geese and other outsiders not deemed worthy of Christian burial are still remembered at the Crossbones Graveyard on Redcross Way. It is now a ‘Shrine to the Outcast Dead’. There’s a candle-lit vigil held on the 23rd of every month to remember the geese, other figures from the counter-culture – and those who were just a little bit different – past and present.

Prostitutes – male and female – worked out of many local brothels, including the Castle at Hope, the Gun, and the Bull’s Head. A more exclusive offering could be found, eventually, at the Holland’s Leaguer. This was more of an exclusive moated fort house than a brothel. King James I was an enthusiastic patron. Its founder was Elizabethan noblewoman Bess Holland. Her wonderful motto was ‘Chastyte is a mere obsolyete thynge.’ Holland Street, by the Tate Modern Turbine Hall entrance, marks her vivid contribution to the neighbourhood to this day.

View of Crossbones Graveyard with Shard building off in the distance. Photo Credit: © Antony Robbins aka Mr. Londoner.

View of Crossbones Graveyard with Shard building off in the distance. Photo Credit: © Antony Robbins aka Mr. Londoner.

Moral compass

General attitudes to sexuality in times past were perhaps more fluid than they are today and social mores ebb and flow just like they do in our own times. An early game-changer, however, came back in the Tudor era. Henry VIII, a man not known for his extensive moral compass, was concerned about his soldiers being infected with diseases. He clamped down on Bankside’s brothels, seeking to regulate what was ultimately un-regulatable. He also introduced a new buggery act in 1533. Henry broke with the church in Rome a few years later and homophobic sentiment grew within the newly-emerging Protestant movement. Some historians argue that the Catholic church was more tolerant of homosexual behaviour, which had been rife among its clergy and was an unspoken feature of monastic life.

Henry’s Buggery Act of 1533 was used as a catch-all against anyone who displeased the king, not just homosexual men. It was this act that Henry used to execute his second wife, Anne Boleyn, on 19 May 1536. Trials for buggery often invoked accusations of witchcraft and unnatural acts and Anne, the subject of cruel character assassination by her arch-enemy Thomas Cromwell, was accused of having sex with her musician Mark Smeaton and her brother George. The two men were beheaded on Tower Hill, just across the water from Bankside, two days before Anne’s own execution. The Queen also ‘confessed’ to having had sex with Sir Henry Norris, Sir Francis Weston, and William Berreton. The latter two were gay so it is unlikely they were guilty of the crimes they were accused of – but they were still beheaded.

Stewswoodcut in Bankside. Photo Credit: © Antony Robbins aka Mr. Londoner

Stewswoodcut in Bankside. Photo Credit: © Antony Robbins aka Mr. Londoner

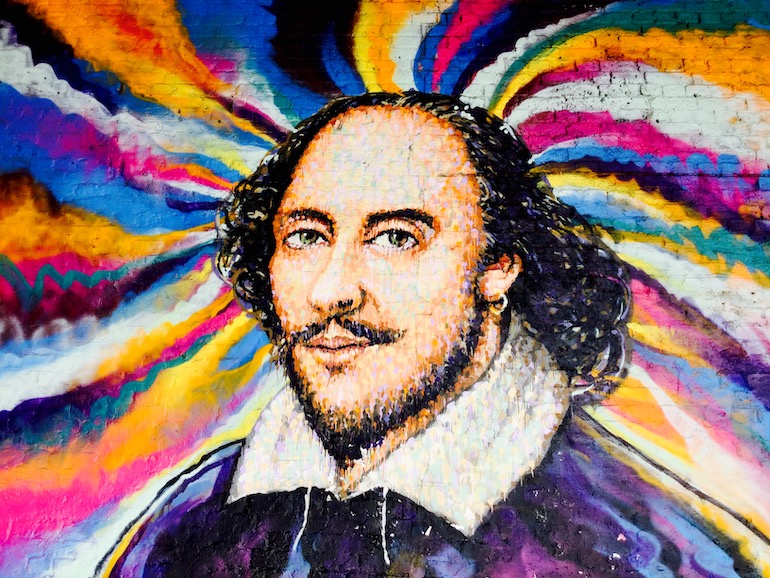

Was William Shakespeare gay?

The Globe Theatre arrived on Bankside in 1599. Audiences were rather less well-behaved then, and the theatre was seen as a den of iniquity. It managed to burn down after the scenery caught fire in a performance of Shakespeare’s Henry VIII. Young men played female roles because women were forbidden from treading the boards. Adept at traversing the scenery in hoopy Elizabethan dresses, they become known as ‘Ye Queene of Ye Drag’. Hence the drag queen was born right here on Bankside.

Historians continue to debate William Shakespeare’s own sexuality. Gay relationships are depicted in his work: the love between Patroclus and Achilles in Troilus and Cressida and again between Antonio and Sebastian in Twelfth Night. Some of William Shakespeare’s sonnets, written as love poems (including a reference to the ‘sweet boy’), suggest a fluid approach to sexuality.

William Shakespeare mural in Clink Street by Jimmy C. Photo Credit: © Antony Robbins aka Mr. Londoner.

William Shakespeare mural in Clink Street by Jimmy C. Photo Credit: © Antony Robbins aka Mr. Londoner.

Restoration

Social morality relaxed following the Restoration when the ‘Merrie Monarch’ Charles II returned to England in 1660, restoring the Crown after fifty years of war and tumult. Bankside’s brothels continued to cater to every kind of taste and every budget. Some seventeenth-century female prostitutes dressed as boys. This makes one wonder what male punters were actually expecting and hoping for.

Some London brothels catered exclusively to a gay clientele. The so-called molly houses invited men to cross-dress and some of these establishments developed an international reputation. Male prostitutes were known as ingles. They signified their availability to other men via special codes and behaviours, sometimes walking the streets and wiggling fingers and thumbs at the back of their frock-coat tails. Just as the seventeenth-century secret language Polari was adapted in the twentieth century as a means for gay men to connect. Earlier epochs had their own ciphers. To engage in gay sex was to enjoy ‘backgammon’ or to ‘play by the back door’. A homosexual man might be called ‘a back door Italian’. None of these phrases were kind. No doubt homophobia was as rife then as it is now in certain sectors of society.

Although there is precious little queer history documented, Southwark and South London as a whole have seen the work of many pioneering gay and lesbian groups over time. The Vauxhall Tavern in neighbouring Lambeth has delivered some truly memorable LGBTQ+ events over the decades. It is home to the collective of performance artists known as Duckie, which promotes alternative gay and lesbian culture and performance. The Ship and Whale in Camberwell put on drag events as early as 1967 – the same year when homosexuality was part-legalised in the UK.

Scrooge street art in Bankside. Photo Credit: © Antony Robbins aka Mr. Londoner.

Southwark Council’s Women’s Committee gave voice to the unheard. Also vocal was the local group the Sappho Sisters, sharing support and advice in a lively 1980s newsletter. These were turbulent times. AIDS and homophobia were unleashed across the gay community. Between 1988 and 2000 Margaret Thatcher’s government unveiled the draconian Clause 28 of the Local Government Act, which prohibited the promotion of homosexual activities by local authorities.

The past is another country – or so they say. However, despite the diverse and more tolerant society that the Capital continues to become, London has lost 58% of its LGBTQ+ venues since 2006. That year, there were 125 venues in operation, while in 2017 there were just 53. The decline continues: Bankside’s legendary XXL nightclub on Southwark Street closed in 2019. It was less a victim of changing social morality. Its loss came on the back of rising rents and property speculation.

Nothing stays the same forever. All is not lost, however, as the area is part of the new Bankside Yard development, in the neighbourhood’s western quarter. As part of the development agreement, another LGBTQ+ space will be created for the community. Plans are not yet set in stone. But watch this space!

All Hallows Church was bombed in the war. Overgrown graveyards, known as ‘itchy parks’ were a place people could hook up. Photo Credit: © Antony Robbins aka Mr. Londoner.

All Hallows Church was bombed in the war. Overgrown graveyards, known as ‘itchy parks’ were a place people could hook up. Photo Credit: © Antony Robbins aka Mr. Londoner.

Editor’s Note:

- In July 2022, Antony Robbins, aka Mr. Londoner, is running ‘Bankside’s Queer History’ – a free one-hour walking tour on behalf of Better Bankside. Get in touch via his Guide London profile to find out more.

- The word ‘queer’, once controversial, is embraced now by the gay community.

Leave a Reply