Which is the most important clock in the world? Many visitors to London would answer ‘Big Ben,’ even though this is officially the name of the bell behind it rather than the clock itself. However, as a London blue badge guide, I would say that the world’s most important timepiece is the John Harrison H4 which can be seen in the Greenwich Royal Observatory museum near where the Prime Meridian is marked on the ground.

Harrison’s sea watch No.1 (H4), with a winding crank. Photo Credit: © Phantom Photographer via Wikimedia Commons.

Although most visitors are more interested in seeing – and being photographed on – the Prime Meridian, it would not be there if it had not been for the efforts of John Harrison, a self-taught clockmaker who built this timepiece over five years in the middle of the eighteenth century. The H4 may look like an oversized pocket watch, but its accuracy and reliability was responsible for saving the lives of many sailors.

Navigators on ships needed to know the precise time in order to calculate their exact position at sea. After the Scilly naval disaster of 1707, a victorious British fleet was returning from Spain only to be shipwrecked within sight of home due to inadequate navigational techniques; the Admiralty offered a £20,000 prize to any clockmaker who could devise a reliable and accurate timepiece for use at sea.

Four ships had been wrecked off the Isles of Scilly in the disaster on the night of 22nd October 1707. At least 1400 sailors lost their lives as a result – and some estimates put the loss of life at 2,000. Records of the crews on Royal Naval ships were sketchy, and many men had been recruited onto them by the notorious press gangs who grabbed anyone they could find and forced them into manning ships of the line.

Amongst the dead was the Admiral of the Fleet, Sir Cloudesley Shovell, a distinguished sailor and Member of Parliament for the town of Rochester. Legend has it that he was washed up alive on the Isles of Scilly but was dispatched by a local woman who had seen a precious ring he was wearing and wanted it for herself. Shovell became a popular hero in Britain and is buried at Westminster Abbey.

The fleet of ships that Shovell was commanding was unable to pinpoint its location accurately and was proceeding towards Britain when rocks were struck off the Isles of Scilly. The four ships that went down with their crews were HMS Association, HMS Romney, HMS Eagle, and HMS Firebrand. HMS Anne narrowly avoided being wrecked in what became the worst ever disaster in British naval history.

Harrison H4 clockwork, at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich. Photo Credit: © Mike Peel via Wikimedia Commons.

Harrison H4 clockwork, at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich. Photo Credit: © Mike Peel via Wikimedia Commons.

After the Isles of Scilly incident and the loss of life involved, efforts were redoubled to improve navigation methods for British ships. The British Parliament passed the Longitude Act of 1714, in which a reward of £20,000 (equivalent to over £3 million today) was offered for the creation of an accurate naval chronometer. John Harrison designed such a clock but was never fully rewarded for his efforts by the Admiralty.

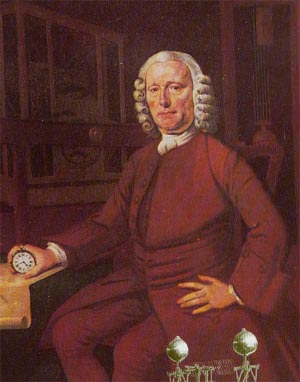

John Harrison English carpenter and clockmaker who invented the marine chronometer. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

John Harrison was born in Yorkshire in northern England but grew up mainly in Lincolnshire where his stepfather worked as a carpenter, a trade which he followed. Fascinated by the workings of clocks and watches from an early age, he was entirely self-taught and worked independently, devoting long hours to perfect the creation of an accurate timepiece that could withstand all the changes of a long sea voyage.

These would include variations in temperature, humidity, and pressure – all of which would affect the accuracy of any clock. Even a small gain or loss of time as a result of these changes could have drastic effects on the calculation of longitude, making an accurate positioning of the ship’s location effectively impossible. This inability to achieve the proper positioning of ships led to the loss of countless lives at sea.

John Harrison is remembered today with a blue plaque on the site of the house where he lived in Red Lion Square, London. His grave is in Saint John’s church in Hampstead, and there is a memorial to him in Westminster Abbey. His achievements were celebrated in the book Longitude by Dava Sobell, which was adapted into a television drama with Michael Gambon portraying Harrison and Ian Hart, his son William.

Blue plaque remembering John Harrison is located on the south side of 11 Red Lion Square, Holborn, London. Photo Credit: © Micronanopico via Wikimedia Commons.

Blue plaque remembering John Harrison is located on the south side of 11 Red Lion Square, Holborn, London. Photo Credit: © Micronanopico via Wikimedia Commons.

In this drama, Jeremy Irons also portrays Rupert Gould, a retired naval officer and amateur horologist who did a great deal to restore the reputation of Harrison in the early years of the twentieth century. Gould single-handedly restored Harrison’s early clocks, which can now be seen in the Observatory of the National Maritime Museum just a few yards from where the clocks stand, still maintaining accurate time.

The Prime Meridian, the line of 0º longitude, was drawn through Greenwich in 1851, although its adoption as an international standard did not take place until 1884. Greenwich was considered the centre of London’s shipping trade, and it was here that the Royal Observatory was established in 1675 by King Charles the Second when Sir John Flamsteed was appointed as the first astronomer royal.

Visitors queuing to take pictures on the line of the Prime Meridian at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, London. Photo Credit: © Daniel Case via Wikimedia Commons.

Visitors queuing to take pictures on the line of the Prime Meridian at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, London. Photo Credit: © Daniel Case via Wikimedia Commons.

To provide an accurate signal of the time for ships moored below on the River Thames, a red ball would drop from the weathervane on top of the tower of the Greenwich Royal Observatory every day at one pm precisely. Once the accuracy of Harrison’s clocks was accepted, navigators on nearby ships could then set their clocks and expect them to remain reliable throughout their long voyages.

The red ball still drops today even though satellite navigation has made precise positioning a relatively straightforward process. Accurate mechanical clocks are no longer considered necessary on ships – although many still carry them as a reminder of Harrison’s contribution to safety at sea. The accuracy of John Harrison’s clocks was to save the lives of many sailors who sailed on British – and other – ships.

Leave a Reply