Since its inception in the first part of the 20th century, the cinema has been a staple of British entertainment. The multiplexes of the 21st century have enjoyed a resurgence following the nadir of the 1980s and early 1990s, but the real golden age of cinema came with the development of the “talkies” in 1927 and the subsequent boom in the construction of new cinemas in the 1930s. That period saw the rise of several cinema chains – the Odeons of Oscar Deutsch and the Granada Cinemas of Sidney Bernstein, plus ABC and Gaumont. Often a town or suburb had one or more of these franchises and they left their mark on London. We are fortunate that some of these magnificent buildings have survived, even if not for their original purpose.

In the early days of cinema, the 1890s and 1900s, most film displays took place in fairgrounds, music halls and theatres or in hastily converted shops – the “penny gaffs”. The film used was highly flammable cellulose nitrate-based, and combined with limelights proved to be a deadly combination with several fatal fires. In 1909 the Cinematograph Act was passed, which specified a strict building code requiring, amongst other things, that the projector be in a fire-resistant enclosure. All commercial cinemas (defined as any business that admitted members of the public to see films in exchange for payment) had to comply with these regulations. To enforce this, each cinema had to be inspected and licensed by the local authority.

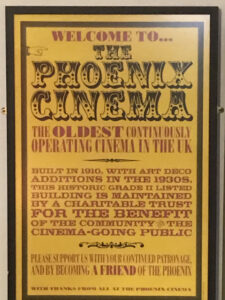

This led to the construction of the first purpose-built cinemas, and North London is fortunate to have a fine survivor from this time. The Phoenix Cinema in East Finchley was built in 1910 by Premier Electric Theatres and although the company went bankrupt, it opened as the East Finchley Picturedrome in May 1912 with 428 seats. The first film shown was about the then recent Titanic disaster. The building went through many name changes and a major overhaul in 1938, giving it an Art Deco exterior and the distinctive Mollo and Egan panelling inside. This redesign was in direct competition with the arrival of the chain cinemas, and the auditorium was reversed so that the slope of the seats no longer followed the natural gradient of the land. The capacity was increased to 528 although today it is just under half of that. The barrel vault roof was retained and is apparently one of only two for purpose-built cinemas in Europe – the other being in Germany. The cinema maintained its independence and despite many threats of closures is now an integral part of the local community, putting on festivals and events. Since 2000 it has enjoyed Grade II-listed status as one of the earliest specific cinema buildings in the country and one that has maintained usage as a cinema for over 100 years.

Phoenix Cinema history plaque in poster style. Photo Credit: © Steven Szymanski.

Phoenix Cinema interior. Photo Credit: © Steven Szymanski.

Phoenix Cinema exterior. Photo Credit: © Steven Szymanski.

There is, though, an older purpose-built cinema building over in West London. On the Portobello Road in Notting Hill stands the Electric Cinema. Designed by Gerald Seymour Valentin in an Edwardian Baroque style, it opened in February 1911. However, it has had periods of closure so the Phoenix claims the title of oldest building continually used as a cinema. Both establishments remained open during each World War. During World War I, the Electric was surrounded by a mob as they believed the German manager was signalling to Zeppelin airships after bombs fell in nearby Arundel Gardens. Perhaps more sinisterly, just after World War II, it is alleged that notorious serial killer John Reginald Christie of 10 Rillington Place infamy worked as a projectionist in the cinema. Christie was certainly a projectionist when he lived in Halifax, but payroll records for the Electric are lost – although a former cinema worker claimed Christie worked alongside him at the Electric (or the Imperial as it was then known). No one knows for sure, but it is very much a local legend, and the now-demolished Rillington Place was nearby. Like the Phoenix, the Electric itself came close to demolition on several occasions and local celebrity residents led campaigns to save it.

Notting Hill is also home to two other well-known independent cinemas. The Gate dates from 1911 in a building converted from a restaurant and was originally known as the Electric Palace. Like the Electric in Portobello Road, it has had periods of closure but is now a successful Art House Cinema and is Grade II listed. Perhaps a more familiar building is the Coronet Theatre just along the main road. Originally built as a theatre, it became part of the Gaumont chain in 1931, then went through a series of different owners and names before becoming the independent Coronet Cinema in 1977. It is under that name that it’s perhaps most famous, featuring in the film Notting Hill. Like all the other early cinemas, it suffered threat of closure, but a Grade II listing helped its survival, and it has now reverted to being a theatre.

All these cinemas operated through World War I and into the 1920s, which of course was still the period of silent cinema. It is generally recognised that the first film with synchronised dialogue, the first “talkie”, was “The Jazz Singer” starring Al Jolson. It was released in 1927 and premiered in Piccadilly in 1928. A year later the Phoenix Cinema showed another Jolson film, “The Singing Fool” – making it the first cinema in North London to show a “talkie”. The public were eager to see this new concept, and so began the golden age of cinema – both in filmmaking and in the construction of cinema buildings, leading to the growth of the chains.

Electric Cinema in Notting Hill, London. Photo Credit: © Steven Szymanski.

Gate Cinema in Notting Hill, London. Photo Credit: © Steven Szymanski.

Coronet Cinema in Notting Hill, London. Photo Credit: © Steven Szymanski.

A new cinema, the Picture House, opened on 1 October 1928 at Brierley Hill in Staffordshire. Its revolutionary design in an Assyrian style by Stanley Griffiths caused a stir, but perhaps its main contribution to cinema in the country was not so apparent: It was the first to be built by Oscar Deutsch. The son of a Hungarian/Jewish scrap metal merchant, Deutsch had been associated with cinema for several years in Liverpool and Birmingham, but the arrival of the talkies gave the young entrepreneur an opportunity to expand. He started slowly, but with ambition. “I want to ring London with Odeons” was his declaration as the 1930s approached. Originally, he planned to use the title “Picture House” for his cinemas, but owners of a similarly named cinema near his second Birmingham site objected. Odeon was a name given to amphitheatres of ancient Greece – a literal translation is “singing place”, and it had been used in cinemas in France and Italy in the 1920s. Oscar liked the name – it was easy to say and coincidentally started with his initials – this later led his publicity department to coin the backronym that it stood for Oscar Deutsch Entertains Our Nation.

Initially, his cinema design was very traditional. Over time, influences from the Modernists of continental Europe, the Amsterdam School of Expressionist Architecture and the Art Deco style first seen at the 1925 Paris Exposition Internationale des Art Decoratifs et Industriels Modernes led to the more radical and progressive designs we associate with cinemas of the time. Deutsch was not the first to use these, but his chain was certainly the largest, with 250 sites across the country by 1937. A popular song at the time, “‘Knocking Down London”, featured the line “There ain’t no money in an Adams house, but there’s oodles in an Odeon.”

Deutsch employed many leading cinema architects of the time, the most well-known perhaps being Harry Weedon and George Coles. They were built economically, though, costing an average of about £20,000 each, around half the cost of a typical cinema at the time (The Tooting Granada reputedly cost £145,000). Odeons sprung up in central London and the suburbs throughout the 1930s, with notable examples at Isleworth and Barnet (1935), Muswell Hill (1936), Woolwich (1937) and Balham (1938). The flagship, though, was the 2,116-capacity Odeon Leicester Square, opened in 1937 with a 120-foot (37m) tower originally planned to be clad in yellow tiles rather than polished granite, but losing 30 feet to meet planning regulations.

Oscar Deutsch died in 1941, and his widow sold the Odeon chain to the Rank Organisation, but the name lives on and indeed was almost synonymous with cinema itself at its peak. It wasn’t without rivals, however. Its main competition was perhaps the Granada chain, founded by media mogul Sidney Bernstein. A diverse and wide-ranging organisation with many interests, it included over 60 cinemas and theatres. Its flagship was the Granada Tooting (1931), with a fantasy interior “resembling a Gothic Cathedral” as did that of the Granada Woolwich (1937), which was billed as “the most romantic theatre ever built” – both those interiors were by the Russian born Theodore Komisarjesky.

Leicester Square Odeon cinema. Photo Credit: © Steven Szymanski.

Woolwich Granada cinema. Photo Credit: © Steven Szymanski.

Interior of the Tooting Granada cinema. Photo Credit: © Katie Wignall.

Granada and Odeon were not the only cinema names on the high street. Other familiar names were Gaumont and through the ABC (Associated British Cinemas) there were names such as Ritz and Regal. The Gaumont group was an offshoot of the French film company of the same name. It developed large “super-cinemas”, with the most famous in London being the Kilburn State Gaumont that opened in 1937 with a capacity of 4,004. The name is said to have been inspired by the Empire State Building and the neon sign on the 120-foot (37m) tower was visible from many miles away.

Many of London’s cinemas fell on hard times after World War II as the development of television led to a drop in attendance. Chains were sold and merged and many of the buildings were lost. Of the Granada cinemas in London, 12 were demolished, 11 (legs eleven?) became bingo halls, including Tooting, while others were converted into storage facilities, fitness centres or car showrooms.

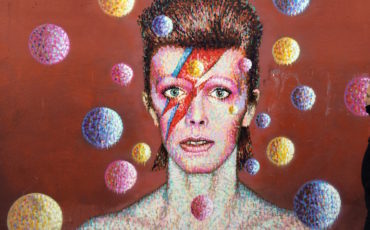

As of 2013, only six still remained as cinemas. The Kilburn State Gaumont, like so many other larger cinemas, survived as a concert venue, and notable concerts there included performances by Frank Sinatra, Duke Ellington, The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and Deep Purple. Two other legendary London rock venues also begun life as cinemas – The Hammersmith Eventim Apollo opened in 1932 as the Gaumont Palace, seating nearly 3,500 and has gone through many sponsorship names, but is still affectionately known by many as the Hammersmith Odeon. Famous shows there include David Bowie’s final performance as Ziggy Stardust in 1973. Over in North London stands what was originally the Finsbury Park Astoria, another goliath of a cinema. It remained as a cinema until 1971 when it became a permanent music venue and was renamed the Rainbow. There had been music staged here before 1971, and it was allegedly the first place Jimi Hendrix burnt a guitar on stage, but as the Rainbow it staged notable performances by, among others, The Who, The Osmonds, Genesis and Bob Marley & the Wailers before it closed in 1982.

Like so many dormant cinema buildings in London, what saved the Astoria/Rainbow was its purchase and conversion by a religious foundation – The Universal Church of the Kingdom of God. The Kilburn State Gaumont had a brief spell as a bingo hall, but is now the Ruach City Church, while the two former magnificent cinemas in Woolwich survive as the Christ Faith Tabernacle (Granada) and New Wine Church (Odeon). Other conversions can be found on Essex Road in Islington and in Uxbridge, but perhaps the most interesting and certainly the most fantastic building converted is at the northwest suburb perhaps better known as an Underground station – Rayners Lane. Here in 1936, the architect Frank Ernest Bromige designed the Grosvenor Cinema. Typical of his designs, it had graceful fins and curves and convex windows. It lasted as a cinema into the 1980s, then underwent several short-lived spells as bars and nightclubs before closing and then being sold in 2000 to the Zoroastrian Trust of Europe, which oversaw a sensitive restoration to convert it to their headquarters.

Kilburn State Gaumont. Photo Credit: © Steven Szymanski.

Finsbury Park Astoria. Photo Credit: © Steven Szymanski.

Rayners Lane Grosvenor. Photo Credit: © Steven Szymanski.

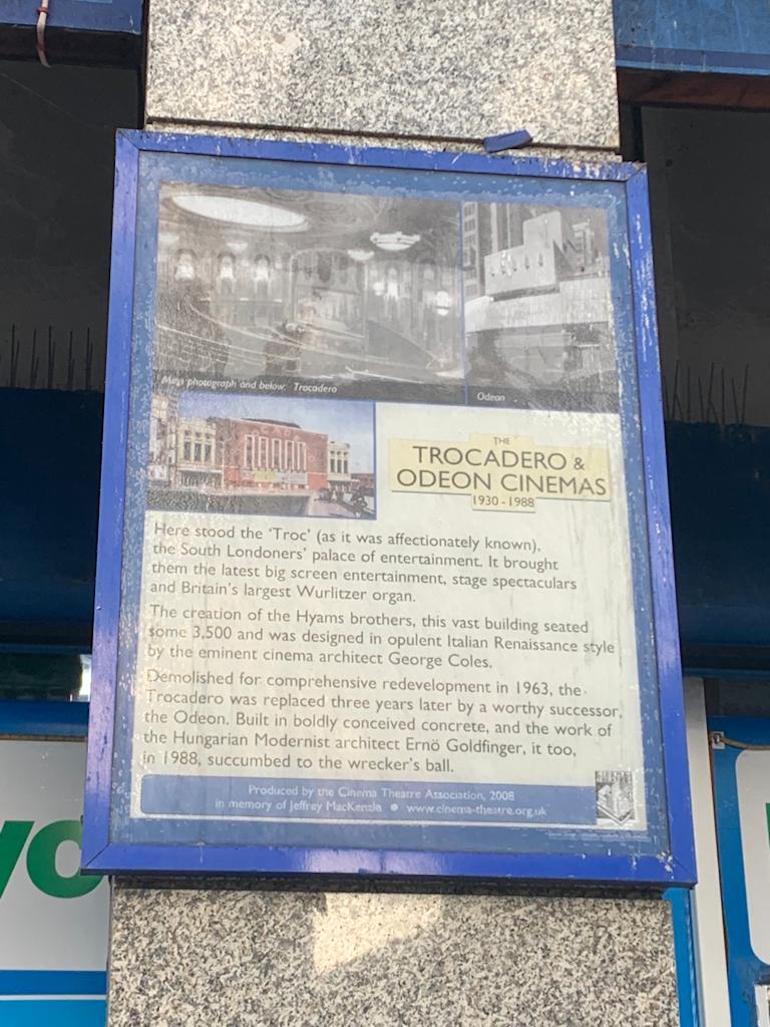

Sadly, even bingo and religion could not save all the cinema buildings in London, and several wonderful examples have been lost. Of these, there are too many to mention but spare a thought for the poor cinema patrons of Elephant and Castle who were graced with the Trocadero in 1930. Though publicity claimed the “Troc”, as it was affectionately known, seated 6,000, its capacity was nearer 3,500 though it did boast Britain’s largest Wurlitzer Organ. Another design of George Coles, this vast building succumbed to the bulldozers in 1963 to be replaced three years later by a brutalist concrete building that was the creation of the maverick Modernist architect Erno Goldfinger. Incredibly, this too was demolished in 1988 (either surely deserved listing) and all that is left is a rather faded historical plaque on the soulless tower block that now stands in its place. Meanwhile, in Kenton the cinema may have gone, but its memory lives on in the bus stop name.

Elephant & Castle – Historic Cinema Plaque. Photo Credit: © Ruth Polling.

Kenton Odeon Bus Stop. Photo Credit: © Steven Szymanski.

Fortunately, a number of the buildings survive both in central London and the suburbs, many as cinemas. This article by no means covers all of them – there are several historic cinemas I have not even visited yet! They are well worth exploring on your next visit to London – offering a lasting testament to the golden age of film and the visionaries who built these fantastic picture palaces.

Essex Road Carlton. Photo Credit: © Steven Szymanski.

Muswell Hill Odeon. Photo Credit: © Steven Szymanski.

Isleworth Odeon. Photo Credit: © Steven Szymanski.

Woolwich Odeon. Photo Credit: © Steven Szymanski.

It will always be the Hammersmith Odeon. Photo Credit: © Steven Szymanski.

Barnet Odeon. Photo Credit: © Steven Szymanski.

Balham Odeon. Photo Credit: © Steven Szymanski.

Uxbridge Regal. Photo Credit: © Steven Szymanski.

All photographs copyright of Steven Szymanski unless otherwise stated. Special thanks to Ewelina Sadlowska at the Phoenix Cinema for allowing access.

Should you wish to see any of these wonderful buildings for yourself the addresses and nearest stations are:

Phoenix Cinema – 52 High Road, East Finchley, N2 9PJ. – East Finchley (Northern Line)

Electric Cinema – 191 Portobello Road, Notting Hill W11 2ED – Ladbroke Grove (Hammersmith and City and Circle lines)

Gate – Notting Hill – 87 Notting Hill Gate, London W11 3JZ – Notting Hill Gate (Central, District and Circle lines)

Notting Hill Coronet – 103 Notting Hill Gate, London W11 3LB – Notting Hill Gate (Central, District and Circle lines)

Isleworth Odeon – 484 London Road, Isleworth TW7 4DH – Isleworth (South Western Railways)

Barnet Odeon – Great North Road, New Barnet EN5 1AB – High Barnet (Northern Line)

Muswell Hill Odeon – Fortis Green Road, Muswell Hill N10 3HP – Highgate (Northern Line)

The Odeon’s in Barnet and Muswell Hill have survived as cinemas and are now part of the Everyman group.

Woolwich Odeon – John Wilson Street, Woolwich SE18 6QQ – Woolwich Dockyard (Southeastern)

Woolwich Granada – 174-186 Powis Street, Woolwich SE18 6JP – Woolwich Dockyard (Southeastern)

These two magnificent former cinemas stand directly opposite each other.

Balham Odeon – Balham Hill and Malwood Road, London SW12 9EA – Clapham South (Northern Line)

Leicester Square Odeon 22-24 Leicester Square, London WC2H 7LQ – Leicester Square (Northern and Piccadilly Lines)

Tooting Granada – 50 Mitcham Road, London SW17 9NA – Tooting Broadway (Northern Line)

Kilburn State Gaumont – 199 Kilburn High Road, London NW6 7HY – Kilburn High Road (London Overground)

Finsbury Park Astoria – 232 Seven Sisters Road, London N4 3NP – Finsbury Park (Victoria and Piccadilly Lines, Thameslink and Great Northern)

Hammersmith Odeon – 45 Queen Caroline Street, Hammersmith W6 9QH – Hammersmith (District and Piccadilly Lines)

Essex Road Carlton – 161-169 Essex Road, Islington N1 2SN – Essex Road (Northern City Line)

Uxbridge Regal – 233 High Street, Uxbridge UB8 1LD – Uxbridge (Metropolitan and Piccadilly Lines)

Rayners Lane Grosvenor – 440 Alexandra Avenue, Rayners Lane HA2 9Tl – Rayners Lane (Metropolitan and Piccadilly Lines)

Leave a Reply