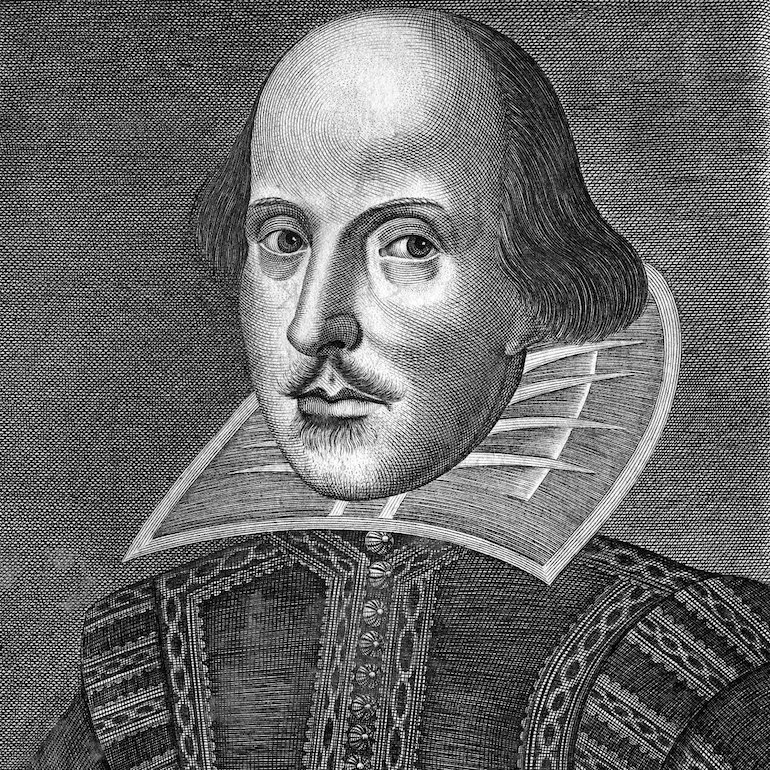

Most of us think that we know what this most famous poet and playwright William Shakespeare, looked like. Our image of him comes from the portrait in the First Folio of his plays, a rather mediocre woodcut by Martin Droeshout, which nevertheless gave a fair likeness, according to his contemporary, friend and rival Ben Jonson. There is the receding hairline (or ‘high forehead’ as the actor David Mitchell puts it in the BBC comedy series Upstart Crow) and the Van Dyck beard. This is a successful man, well-dressed in expensive clothes, someone who has established himself in the booming Elizabethan theatre world.

But what did Shakespeare look like in his early years? We know very little about William Shakespeare before he came to London. Although it has always been assumed that he attended the Grammar School in Stratford, there is no documentary evidence that he actually did, indeed no record of his existence between the registrations of his birth in 1564 and his marriage to Anne Hathaway eighteen years later. After the marriage and the birth of his three children, we lose track of Shakespeare completely in what historians refer to as ‘the lost years’.

Shakespeare first made his name in London in the mid-1580s at what was simply called The Theatre in the aptly named Curtain Road, Shoreditch. This building was then moved to Southwark in 1599 near where the modern Globe was built by American actor and Shakespeare enthusiast Sam Wannamaker, whose daughter Zoe is a well=known actress. There are references to Shakespeare in his London days and a few specimens of his signature but no definite images of him from this period. The last image of him is above his grave in the Holy Trinity church, Stratford which many blue badge guides take groups to. His widow Anne Hathaway is reported to have said that it was a good likeness of him, while others have compared it to unflatteringly to the face of a prosperous pork butcher.

Apart from the Droeshout woodcut and the Stratford bust, there are no portraits which can be definitively identified as representing William Shakespeare. Even the Chandos painting, the very first picture acquired by the National Portrait Gallery, is only assumed to be of him because it represents a man who looks very much like our much-loved playwright and poet.

These are the images which claim to represent William Shakespeare;

The Droeshout

There were two Martin Droeshouts in a family of Dutch engravers. This portrait, which appears on the frontispiece of the First Folio of Shakespeare’s plays published in 1623 (seven years after his death), is generally thought to be by the younger Martin. It is not well-regarded as a work of art but was said by Ben Jonson to be a fair likeness.

Status: definite

William Shakespeare portrait by Martin Droeshout known as The Droeshout Engraving. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

William Shakespeare portrait by Martin Droeshout known as The Droeshout Engraving. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

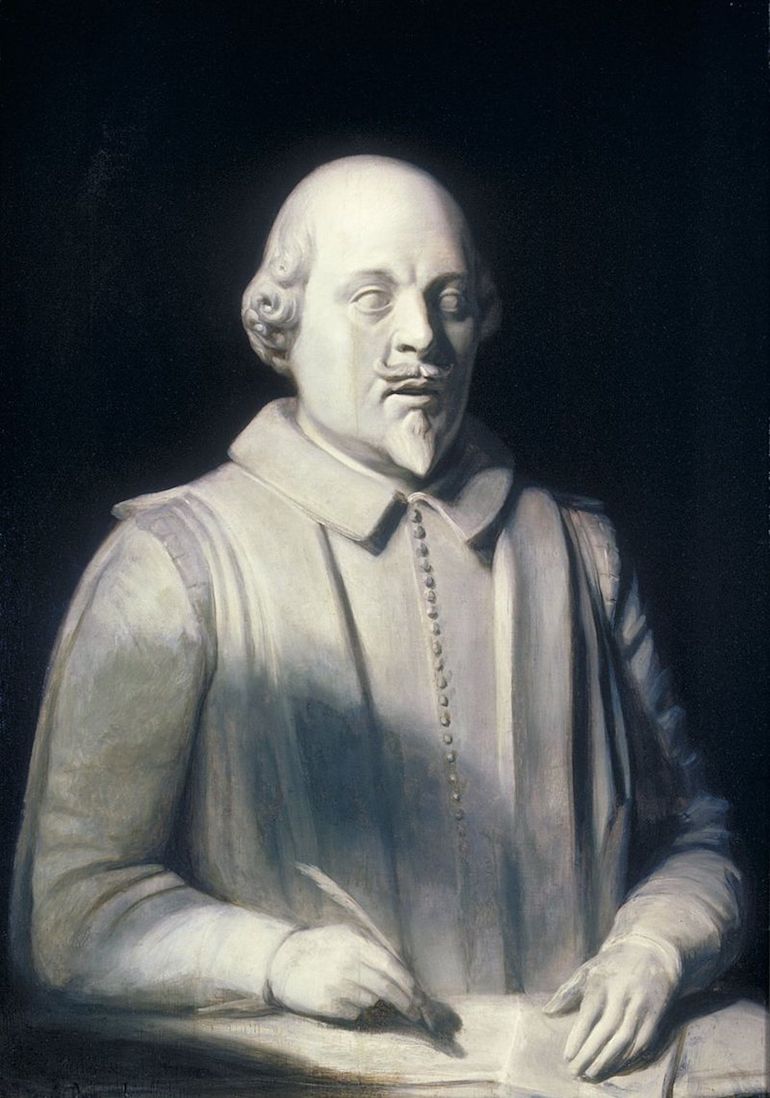

The Stratford Bust

The other undisputed image of William Shakespeare was also by a Dutch artist, Gerard Johnson (originally Janssen) who may have known the writer, as the family workshop was close to the Globe Theatre. The monument, made from Cotswold marble, is mentioned in the introduction to the First Folio so must have been completed by 1623.

Status: definite

William Shakespeare portrait by Gerard Johnson known as The Stratford Bust. Photo Credit: © Wikimedia Commons.

William Shakespeare portrait by Gerard Johnson known as The Stratford Bust. Photo Credit: © Wikimedia Commons.

The Chandos Painting

This was donated to the National Portrait Gallery by the Duke of Chandos in 1856 when the gallery was founded. Probably painted in the early 1600s by John (or Joseph) Taylor it may once have belonged to William Davenant, a playwright and poet rumoured to be Shakespeare’s natural son. The portrait has never been definitively identified as Shakespeare and is assumed to be him only because of its likeness. Note the raffish earring

Status: Probable but not proven

William Shakespeare portrait by John Taylor known as the Chandos Portrait. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

William Shakespeare portrait by John Taylor known as the Chandos Portrait. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Cobbe and Jansen Portraits

This painting, on view at New Place in Stratford, has been identified as one of Shakespeare by the Birthplace Trust. It belonged to the Anglo-Irish Cobbe family and may have been painted from life – although some scholars say that it actually portrays Sir Thomas Overbury. A version of this portrait by Cornelius Janssen belongs to the Shakespeare Folger Library of Washington DC, although the distinctive receding hairline was painted on later.

Status: possible

William Shakespeare portrait known as the Cobbe painting. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

William Shakespeare portrait known as the Cobbe painting. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Grafton and Sanders Portraits

These are portraits of men made during Shakespeare’s lifetime which have been identified as him. There is no further evidence that they are, although the Sanders is traditionally attributed to John or Thomas Sanders, who may have been a scene painter for Shakespeare’s company.

Status: doubtful

William Shakespeare portrait attributed to Sanders. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

William Shakespeare portrait attributed to Sanders. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Soest Painting

This highly regarded portrait was painted at least thirty years after Shakespeare died, possibly after the theatres reopened following the Restoration, by yet another Dutch artist Gerard Soest. It was owned by Joseph Wright, an artist who lived in Covent Garden and now belongs to the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust.

Status: definite but not from life

William Shakespeare portrait by Gerald Soest. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

William Shakespeare portrait by Gerald Soest. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

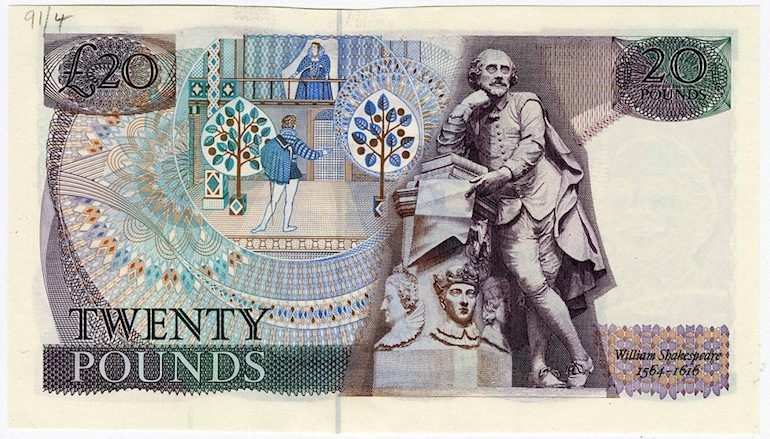

The Old Twenty Pound Note/Garrick statue

Photo Shakesepere£20

These are probably the best-known images of Shakespeare based on a statue modelled by the actor-manager David Garrick, who did so much to re-popularise Shakespeare in the 1700s. Garrick was the first actor to be buried in Westminster Abbey, beneath the statue of him posing as Shakespeare. A copy of this is in the British Library, having been moved from the British Museum when the Library was built twenty years ago. This image of the bard was used on the series D £20 note from 1970 to 1993 together with a picture of Romeo and Juliet. Shakespeare was succeeded by Michael Faraday, then Edward Elgar. In 2020, the artist JMW Turner will be on the new plastic £20 note.

Status: definite but not from life

William Shakespeare statue at the British Library in London. Photo Credit: © Edwin Lerner.

William Shakespeare statue at the British Library in London. Photo Credit: © Edwin Lerner.

Leave a Reply