Charles de Gaulle, a junior minister in a collapsing government and a relatively junior general in an army that was ceasing to exist, landed at Heston airport after a gruelling and perilous flight from Bordeaux, on Monday 17 June 1940. Few of his British hosts knew who he was, Winston Churchill being the exception. During his visits to France, Churchill had immediately noticed “a young, energetic general called de Gaulle.” `(In Gabriel Le Bomin’s biopic of de Gaulle, which features the early days of the two men’s relationship, Churchill is brilliantly played by Tim Hudson – who is also a London Blue Badge Guide!)

The following evening de Gaulle was at Broadcasting House recording his historic first speech, in which he called upon the French to continue to fight, in defiance of the armistice being negotiated by the Pétain regime. Over the following three years, as the leader of the Free French, de Gaulle lived and worked mainly in London. And, as a London Blue Badge Tourist Guide can show you, there are many sites and districts of London which have a de Gaulle connection.

Broadcasting House in London. Photo Credit: © Keriluamox via Wikimedia Commons.

Broadcasting House in London. Photo Credit: © Keriluamox via Wikimedia Commons.

The first, temporary, HQ of the Free French in London was St Stephen’s House on the Victoria Embankment, nowadays part of the Parliamentary Estate, and known as Norman Shaw South. In July they were able to move into the building that remained the nerve centre of the Free French until 1944: 4 Carlton Gardens, a building in the contemporary neo-Classical style dating from 1923-4.

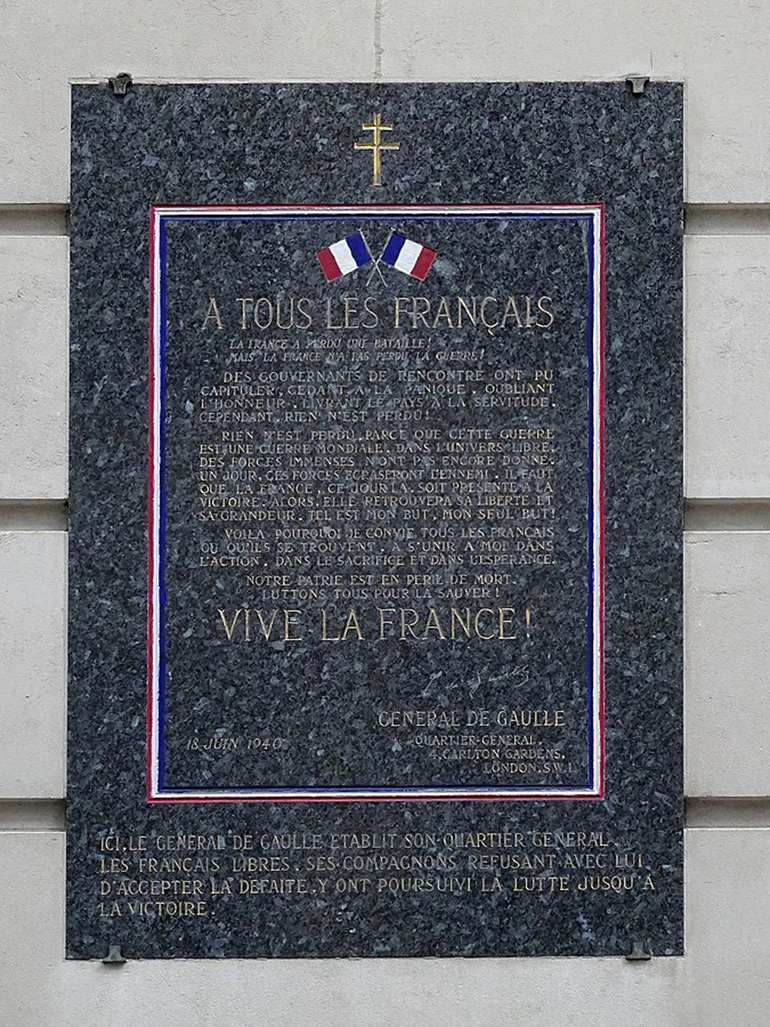

Charles De Gaulle black plaque – 4 Carlton Gardens St James’s London SW1Y 5AA. Photo Credit: © Spudgun67 via Wikimedia Commons.

Charles De Gaulle black plaque – 4 Carlton Gardens St James’s London SW1Y 5AA. Photo Credit: © Spudgun67 via Wikimedia Commons.

There we can see two memorial plaques which commemorate de Gaulle and the Free French. The blue plaque states that de Gaulle, as President of the French National Committee set up the HQ of the Free French Forces here in 1940. The rectangular plaque, placed there in 1947, bears, in French and English, the stirring words of de Gaulle’s Appeal of June 18th. Across the road on a high plinth is Angela Conner’s statue of de Gaulle, unveiled in 1993. It portrays de Gaulle in the unform of a général de brigade (brigadier), his rank in 1940.

Statue of Charles de Gaulle in London. Photo Credit: © Giogo via Wikimedia Commons.

Statue of Charles de Gaulle in London. Photo Credit: © Giogo via Wikimedia Commons.

After his first few days in London De Gaulle stayed at the Rubens Hotel in Buckingham Palace Road, It was here on 20 June that he was reunited with his family, Mme Yvonne de Gaulle, his teenage children Philippe and Elisabeth and little Anne. They too had had a perilous journey – by sea from Brest to Plymouth. Philippe de Gaulle later remembered that the meeting at the Rubens was one of the few occasions on which the children saw their parents kissing.

The family’s first set up home in Birchwood Road, Petts Wood and from here de Gaulle could commute daily to Carlton Gardens. Nearby Chislehurst junction, however, was an obvious target for Hitler’s Luftwaffe, and the frequent explosions were particularly distressing to little Anne de Gaulle, who had Down’s syndrome.

So Yvonne de Gaulle and the children moved to a house in Shropshire, some 300 kilometres from London. There followed a period of isolation for Mme de Gaulle and the children as de Gaulle himself seldom had time to visit them. The family moved again, to Little Gaddesden, a village in Hertfordshire where de Gaulle was able to spend his weekends with them. From Mondays to Fridays he lived at the Connaught Hotel.

Finally, in September 1942, the family took up residence at a London address: 99 Frognal, in Hampstead. Always a devout Catholic, de Gaulle regularly attended mass at the nearby Catholic church, St Mary’s, a church built in the 1790s for French Catholic émigrés.

St. Mary’s Hampstead, London. Photo Credit: © Gareth E. Kegg via Wikimedia Commons.

St. Mary’s Hampstead, London. Photo Credit: © Gareth E. Kegg via Wikimedia Commons.

For centuries London has welcomed French émigrés. Soho in particular has been home to a thriving French community since the early eighteenth century. There were French shops and restaurants, and it was here that many of the Free French spent their off-duty hours. One spot in Soho which preserves particularly warm memories of the Free French is the former York Minster pub, subsequently renamed the French House in their honour.

The French House pub in the Soho area of London. Photo Credit: © Ewan Munro via Wikimedia Commons.

The French House pub in the Soho area of London. Photo Credit: © Ewan Munro via Wikimedia Commons.

De Gaulle himself was seldom to be found in Soho. He usually dined at the Connaught, sometimes in a Pall Mall club, sometimes in one of London’s celebrated French restaurants such as the Coq d’Or or the Savoy. He understood that the working lunch was an important social mechanism of the British Establishment and he conducted many important discussions, about the conduct of the war, about the future of France and Britain over lunch … in French, of course.

The Connaught Hotel in London. Photo Credit: © Soham Banerjee via Wikimedia Commons.

The Connaught Hotel in London. Photo Credit: © Soham Banerjee via Wikimedia Commons.

In fine weather, de Gaulle would often walk from Carlton Gardens to have his lunch at the Connaught. His immensely tall figure, in the familiar uniform of a French officer, was frequently recognised. His uncomfortable relationship with the British government is now a matter of historical record but, at the time, ordinary British people knew little of this. As de Gaulle strode at lunchtime through St James’ and Berkeley Square he would often be greeted and applauded by passers-by.

As well as 10 Downing Street and Broadcasting House, a number of London’s most famous buildings have a connection with de Gaulle. He spoke a number of times at assemblies of the Free French community in the Albert Hall and his speeches were included in the daily broadcast to occupied France, Les Français parlent aux Français. On one occasion, he addressed – in English – members of the Lords and the Commons at the Houses of Parliament. The statue of Marshal Foch in Grosvenor Gardens was an important rallying point for the Free French. During the war years, a regular parade took place there on Bastille Day, 14th July, and de Gaulle laid the wreath in memory of the former Commander-in-chief.

Equestrian statue of Ferdinand Foch, London. Photo Credit: © Carcharoth via Wikimedia Commons.

Equestrian statue of Ferdinand Foch, London. Photo Credit: © Carcharoth via Wikimedia Commons.

In April 1960, as President of the French Republic de Gaulle, made a state visit to London. This visit took place at a delicate time: it was at the height of the Algerian crisis and at the time when the British government was considering its first attempt to join what was then the European Common Market. On arriving at Victoria Station de Gaulle accompanied the Queen in an open carriage to Buckingham Palace. During the four days of the visit, he attended a gala ballet performance at Covent Garden, visited the Royal Hospital, Chelsea and addressed the Houses of Parliament – in French, this time – at a ceremony in Westminster Hall, complete with a military band.

Horse Guards Parade in London. Photo Credit: © Romainbehar via Wikimedia Commons.

Horse Guards Parade in London. Photo Credit: © Romainbehar via Wikimedia Commons.

The climax of the 1960 visit was a full-scale review of the Household Brigade at Horse Guards: de Gaulle was the first and only foreign head of state ever to have been invited to do this. Accompanied by Prince Philip, de Gaulle rode down the Mall in an open carriage in the uniform of a général de brigade. Out of respect for his guest, Prince Philip also wore a brigadier’s uniform on that day. As the carriage passed the steps leading up to Carlton Gardens de Gaulle raised his hand to his képi in a solemn salute to his old comrades.

There are many ways to explore London in the long footsteps of Charles de Gaulle. How better than to do this in the company of a London Blue Badge Tourist Guide – we can bring the past back to life!

Leave a Reply