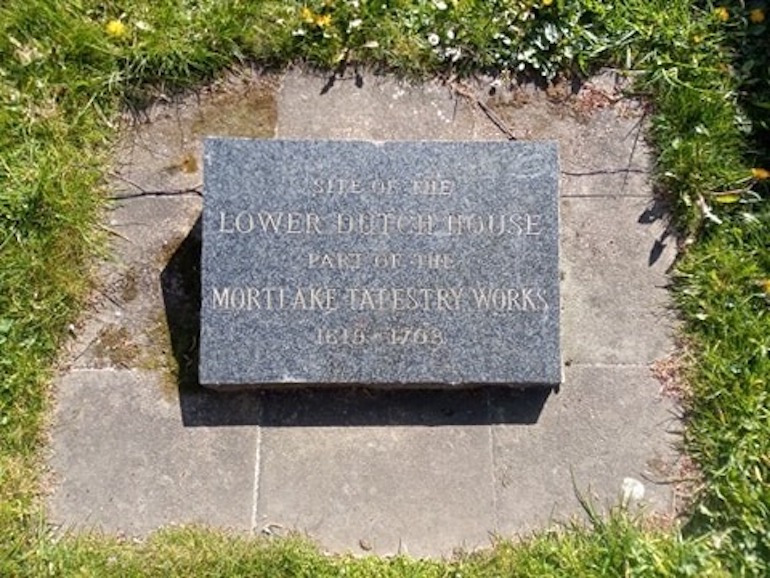

Opposite the church of St Mary The Virgin, Mortlake a path called Tapestry Court leads to the River Thames. Here you will find a plaque memorialising the seventeenth century Lower Dutch House, one of the former buildings of the Mortlake Tapestry Works.

Mortlake Tapestry Works was founded in 1619 by the secretary to the Prince of Wales, Sir Francis Crane, with encouragement from James I, in the hope of rivalling a similar venture started in Paris in 1607 under the patronage of Henry IV of France. The riverfront site was deliberately chosen as it had a humid environment. This was essential for weaving to relax the tension of the warp. The river itself was the main means of transporting bulky products and materials.

Mortlake Tapestry Works plaque. Photo credit: © Christopher Hayden.

Mortlake Tapestry Works plaque. Photo credit: © Christopher Hayden.

Tapestries are textile works of art woven on a loom. Throughout the medieval period and early Renaissance the cities of Brussels, Antwerp, Ghent and Bruges manufactured the best tapestries in Europe. Traditionally, tapestries were far more luxurious commodities than paintings due to their cost, the expensive materials used – silk, gold and silver thread – and the number of workers involved plus the time it took to complete a piece. They were ideally suited to keep rooms warm by acting as insulation and were easy to carry, store and to arrange around furniture and rooms.

Crane brought over to Mortlake 140 Flemish weavers and their families lived on the site in the former estate of the Renaissance scholar and occultist Dr. John Dee. The Archbishop of Canterbury gave a special dispensation to allow the mostly Lutheran weavers to worship in their own language and according to their credo.

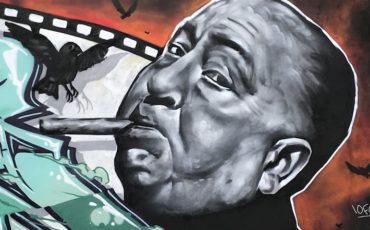

Many great works were executed in Mortlake and are now found across Europe in galleries and private collections. The Tapestry Works, however, is associated with the Renaissance artist Raphael and his Acts of the Apostles cartoons produced in 1515. Originally, these cartoons were used to make the beautiful tapestries that hang in the Sistine Chapel commissioned by Pope Leo X.

The Miraculous Draught of Fishes. Photo Credit: © Christopher Hayden.

The Miraculous Draught of Fishes. Photo Credit: © Christopher Hayden.

Raphael’s Cartoons were so revered that more sets were produced for King Henry VIII, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and other monarchs. Later the cartoons went missing but eventually, seven of them appeared for sale in Genoa, where Charles I’s agents purchased them and brought them back to England in 1623. Oliver Cromwell later donated Charles I’s set of the Acts to the King of France after the abolition of the monarchy in England, but the cartoons were finally restored to the Royal Collection in 1660. Now they can be admired in a dedicated gallery in the Victoria & Albert Museum, South Kensington, where they are displayed with The Miraculous Draught of Fishes tapestry, which was produced for the Earl of Pembroke.

When Crane died in 1636, Charles I acquired the Tapestry Works which became known as the King’s Works and the future of the business seemed secure. Unfortunately, Charles’s arbitrary powers in matters of religion and governance set him on a collision course with Parliament, and the ensuing conflict meant the king had to put aside his art collecting pastime.

During the 1640s the weavers at Mortlake struggled, going through some real hardship and having to produce lower quality work, often with the backing of members of the Dutch Church in the City of London. Returning to the continent was not an option, as what are now the Low Countries were occupied by a brutal Spanish regime.

The Healing of the Lame Man. Photo Credit: © Christopher Hayden.

The Healing of the Lame Man. Photo Credit: © Christopher Hayden.

With the rise in status of painting and portraiture in the late 1600s, the Mortlake Tapestry Works never recovered, with many weavers moved to the City of London and Soho to work in factories whilst one Philip Hollenbirch is recorded as becoming a shoemaker in Mortlake. Sadly, in 1703 during the reign of Queen Anne, the works were closed down.

Besides the plaque, nothing remains in Mortlake that would alert us to the legacy of this extraordinary industry, yet it is amazing to think that for a brief period of time in a remote English village along the Thames we had a workshop that rivalled Europe’s great artistic centres.

Note: Some of the best examples of Mortlake Tapestry Works are currently on display at the Victoria & Albert Museum which you can explore with a Blue Badge Tourist Guide.

Leave a Reply