2021 year marks the 550th anniversary of one of the most significant battles in British history. On the 14th of April 1471, the Yorkist army led by Edward IV defeated a Lancastrian army just north of the town of Barnet effectively ending the first part of that turbulent period of history colloquially known as the Wars of the Roses. Strictly speaking, there was one more encounter between the rival armies a month later at Tewksbury, but Barnet was important as it saw the death of Richard Neville – Warwick the Kingmaker – which all but ended Lancastrian hopes of a return to monarchy.

During the summer, I visited the traditional site of the battlefield and it got me thinking that London has of course since its inception always been a key strategic location but despite our volatile history, how many battles have taken place in or near the city? Obviously, London has grown over the years and defining the city is not easy (that is a whole other project) so I decided to limit myself to confrontations within the boundaries of the modern M25. This limitation left a surprisingly few number of what is historically regarded as battles and even some of those are questionable. Even more remarkably, two (some say three) of them took place in the same place in West London and another just a couple of miles away.

Arguably, I could include such events as The Peasants Revolt, Jack Cade’s Rebellion, Thomas Wyatt’s Rebellion and the Gordon Riots with their Central London locations but, with one honourable exception, these are more instances of civil unrest than full-scale military engagements, although the boundaries are blurred. London of course, also saw significant military activity during both World Wars with Zeppelin raids in the First World War and the Blitz/V Weapon attacks in the Second World War but while this activity caused significant loss of life and considerable damage, for the purposes of this article I am not regarding them as battles.

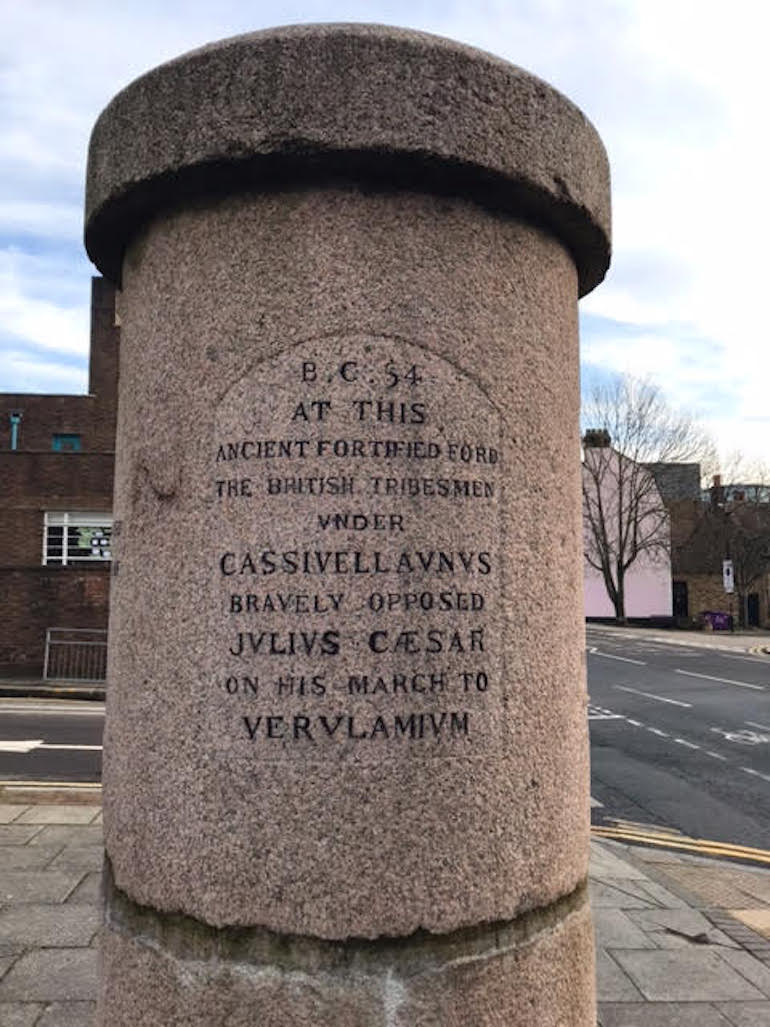

For the first potential battle site, we must go back to even before what is generally recognised as the founding of London and to the first Roman invasion in 54BC by Julius Caesar. Legend has it that Caesar crossed the Thames here as it was one of only two fording places (the other being Walton) but he had to fight a battle against a local chieftain Cassivellaunus. It is said that the locals put wooden stakes against the riverbank to prevent a crossing and, indeed, stakes were found along the riverbank at both Walton and Brentford but these are now believed to be medieval in origin. The great Roman historian Tacitus also questioned Julius Caesar’s somewhat unreliable memory and glorification of events, so it is open to debate whether any battle took place in Brentford. The locals certainly think so though and outside the County Court is a memorial column erected originally closer to the river in 1909 that lists among other things the crossing of the Thames and defeat of Cassivellaunus by Julius Caesar in 54BC. But this is not the only thing it lists, as Brentford will return to our story later.

Brentford Monument with Julius Caesar Inscription. Photo Credit: © Steven Szymanski.

Brentford Monument with Julius Caesar Inscription. Photo Credit: © Steven Szymanski.

However, while in Roman times we must make mention of the great native British warrior queen Boudicca and the rebellion against established Roman occupation over a century after Caesar may have fought at Brentford. During her uprising (once again Tacitus is the source) Roman London was destroyed by fire in around AD 61 but the governor Suetonius had already fled the city, as he did not feel it was a suitable to face the army of Boudicca and her Iceni tribe. However, there was a final battle and many people have suggested the battle took place near what is now King’s Cross – an area formerly known as Battle Bridge.

Tacitus’s description of the spot fits with the accepted geography of the time with one major omission: he makes no mention of the River Fleet which would have been a major feature of any large battle in the area. The battle has also been cited as being near Parliament Hill Fields but, in truth, the location is unknown and a wide number of locations around the country have been put forward. As an aside after her defeat and suicide the warrior queen was supposedly buried somewhere beneath platforms 9 and 10 of the station (9¾ possibly – all you Harry Potter fans!) but there is again no historical evidence of this and it would appear to be a 20th-century fabrication.

For what can be regarded as the first actual battle within what is now Greater London with any definite historical proof, we have to go forward nearly one thousand years to 1016 and return to Brentford. Here an English army led by Edmund Ironside defeated the Danish army of Canute. We have already seen that Brentford was an important river crossing but it was also on the main road from the west into London making it strategically important. Edmund and Canute fought a series of battles throughout 1016 and although Edmund won this one, Canute ultimately won the conflict and became king. Once again, this action is marked on the Brentford Monument.

Brentford Monument with Edmond Ironside Inscription. Photo Credit: © Steven Szymanski.

Brentford Monument with Edmond Ironside Inscription. Photo Credit: © Steven Szymanski.

Incredibly, six hundred years later, Brentford was the scene of yet another conflict – the second (or is it third?) Battle of Brentford which occurred during the early part of the English Civil War on 12th November 1642. Having left London with no agreement with Parliament, King Charles I headed north and raised an army with the intention of returning to the capital and taking it by force. Parliament too had raised an army led by the Earl of Essex and the two forces eventually met at what was the inconclusive Battle of Edgehill. Essex and his army headed towards Warwick allowing the king’s troops to continue their journey towards the ultimate prize – London.

The Royalist army led by the king’s nephew Prince Rupert made its way through the Thames Valley capturing Banbury, Oxford, Abingdon, Aylesbury and Maidenhead, though Windsor proved to be too impregnable. This allowed Essex to get back to London and regroup while the Royalists agreed to negotiations and moved up to Colnbrook on 11th November. Charles ordered Rupert to take Brentford due to the already noted strategic importance, and because of a stone bridge over the River Brent (a tributary of the Thames) on that main road to the west. Essex has set up camp in Kingston but sent a detachment to guard the Brentford bridge.

Rupert’s army had already looted the town the previous day when they met the Parliamentary forces. Initially, the Parliament forces held out but Rupert sent up reinforcements into what was developing into a running skirmish through the town and forced the defenders out into open land. Fighting also occurred at nearby Syon House with the Royalists ultimately prevailing. Though the battle lasted all day most of the Parliament troops were able to escape. Rupert and his men then looted the town for more supplies which turned the local population against them and led to another confrontation the next day.

That battle – and I use the word advisedly – took place a couple of miles up the road around what is now Chiswick High Street and was known as the Battle of Turnham Green. In reality, it was little more than one gigantic standoff as Essex assembled a force estimated at between 24,000 and 27,000 while the Royalists were between 12,000 and 13,000 in strength. In the long and bloody history of this country, only the Battles of Towton and Worcester have seen more combatants. The Parliamentary forces included sailors, the London militia, and many poorly armed locals while the Royalists, though probably containing more cavalry, lacked ammunition and were fatigued. The two forces faced each other across the Green, with the vast Parliament forces lined up somewhere near where Turnham Green station is today.

Essex positioned the London militia prominently so King Charles would know that the city stood with Parliament. Neither side was willing to commit, Essex because he had too many untried and under-trained troops, plus his principal aim was only to block the Royalist advance on London. Charles realized he was outnumbered, plus any engagement would lead to a potentially large loss of life among London’s citizens, a population he needed to gain the support of if he were to retake the capital. There was some minor skirmishing but probably less than 100 fatalities and, with the weather closing in, the Royalist withdrew ultimately to Oxford. Never again would they come close to taking London and without the capital, they would never win the war.

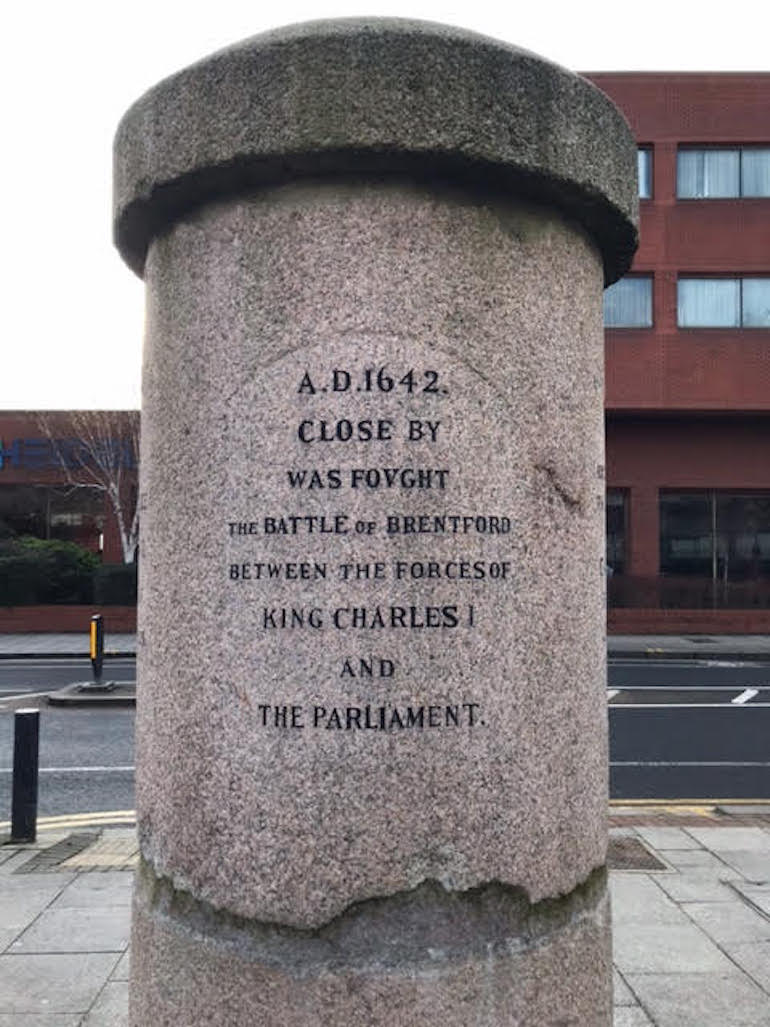

That Brentford monument makes mention of the Battle of Brentford while some very good history boards at Brentford Bridge, around Chiswick Green and outside Turnham Green station tell the story of the two battles.

Brentford Monument with Civil War Inscription. Photo Credit: © Steven Szymanski.

Brentford Monument with Civil War Inscription. Photo Credit: © Steven Szymanski.

So, what else is there regarding actual battle sites in London? As I previously mentioned, there have been several civil uprisings occurring in or around the city, but it is questionable whether they can really be described as battles. Perhaps the only event during any of these that was any semblance of what could be called a battle occurred during Jack Cade’s uprising in the summer of 1450 – what is sometimes referred to as the Battle of London Bridge.

Cade’s Rebellion occurred during the difficult reign of Henry VI when a weak monarch combined with a corrupt system and high taxes, plus military losses in France, led to a popular uprising in the South East. Led by Jack Cade, a growing band of citizens unhappy with the administration marched towards London. The rebels had a list of demands regarding the removal of corrupt officials and when these were ignored a force of about 5,000 camped on Blackheath. The king sent a force to quell them but it was defeated and the rebel force, growing in confidence, marched on London. Despite resistance, Cade crossed London Bridge on July 3rd 1450 and his forces cut the ropes of the drawbridge to ensure it remained open. Following sham trials, key officials were executed, which turned the population against Cade This, together with a failure to prevent his army from looting, meant that when they crossed London Bridge back into Southwark steps were taken to prevent them re-entering the city. Lord Scales, the keeper of the Tower of London was approached to defend the city and he appointed Matthew Gough, a veteran of the French Wars, to defend the Bridge and prevent the rebels re-entering the city.

A battle began on London Bridge around 10 pm on the 5th of July and raged all night. At only eight feet wide and covered in shops and houses it was not an ideal battleground more so that Scales and Gough had set up defensive barricades across the bridge, among which the two forces fought for control. Initially, Cade had the advantage as his army, boosted by prisoners freed from the Marshalsea, reached and held the drawbridge at the Southwark end-setting fire to houses and shops. Gough had been ordered to hold the southern end of London Bridge, but he and his men were forced back almost to the Church of St Magnus the Martyr on the north bank before they rallied and pushed the rebels back to Southwark and were able to bolt the gates.

Hundreds died in the bloody battle, including Gough, with many dying in the flames or drowning as they jumped to escape the smoke. Cade himself escaped the Battle of London Bridge but his rebellion was doomed to fail if he could not re-enter the city and he was hunted down and killed in Sussex five days later. So that is perhaps the only time there has been anything approaching a battle in Central London but for the only true pitched battle within the area encompassed by the modern M25, I return to the Battle of Barnet in 1471.

Jack Cade’s Rebellion had occurred because of the troubled reign of Henry VI and this ultimately manifested itself into the period of history we now know as the Wars of the Roses. Rival branches of the same family descended from King Edward III fought for the ultimate power of the throne of England. Most historians now agree that the conflict between the House of Lancaster (red rose) and the House of York (white rose) began in 1455 and continued sporadically for the next thirty years or so. Having said that, the restoration of Edward of York as King Edward IV in 1471 is regarded by many as the end of the Wars of the Roses proper and that effectively came about with the Lancastrian defeat at Barnet. As an aside, mention should perhaps be made of St. Albans which saw two conflicts during the early stages of the Wars in 1455 and 1461 respectively. There was one victory for each side but of course, St. Albans is just outside the modern M25 so, although close to London and significant for the purposes of this article, I will not include them.

The Wars of the Roses are a very complex period of English history but by 1471 the position was this. The Lancastrian king Henry VI was deposed in 1461 and ultimately imprisoned in the Tower of London. Edward, Duke of York became King Edward IV but he had upset his powerful ally Richard Neville, also known as Warwick the Kingmaker. Neville, Earl of Warwick, felt slighted when Edward married Elizabeth Woodville rather than his negotiated choice of a French bride. This turned to further embarrassment when the Woodville family became court favourites over his family and, in a classic tactic, he switched sides and pledged his support to the Lancastrian supporters of Henry’s wife Margaret.

Gathering the support of another turncoat, namely Edward’s brother George, Duke of Clarence, he returned from exile and landed in Devon in the Autumn of 1470. Then his forces marched to London and freed Henry from the Tower and proclaimed him the king. Edward and his brother Richard were in turn forced to flee into exile. However, by the spring of 1471, backed by the financial support of his brother-in-law, Charles Duke of Burgundy, Edward had raised a small army and landed in Yorkshire. The army quickly grew and he marched south to face the Lancastrian army. They failed to draw Warwick and his army out of their Midlands stronghold for a battle but on his way south Edward did regain the support of his brother George.

Battle of Barnet – Edward (centre) leads his army to victory, as Warwick’s men flee to the right. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Battle of Barnet – Edward (centre) leads his army to victory, as Warwick’s men flee to the right. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Stopping for a quick visit to Westminster to see his wife and new-born child, Edward made his way to the Tower to meet his cousin and ‘fellow’ monarch Henry. The pathetic figure of the king allowed himself to join Edward’s growing army as a hostage (as London supported the young Edward over the old and feeble Henry). As they made their way to Barnet, a small village some 10 miles (16 kilometres) north of the city, Edward had learnt that Warwick and his army had followed them south to do battle for the throne of England.

Late on Easter Saturday, the two armies came into contact with each other, but it was too late to engage and they camped close to each other on the field just north of Barnet. Edward ordered a surprise attack at first light and the Yorkists camped close to the Lancastrian lines. So close, in fact, that the Lancastrian cannons which kept up an all-night bombardment overshot the Yorkist positions. Daybreak on Easter Sunday brought heavy mist and, combined with the two armies not being directly opposite each other, the left side of each battle line could be outflanked. The Lancastrian right flank commanded by the Earl of Oxford routed the Yorkist soldiers of Lord Hastings and pursued them south off the battlefield to the town.

Some Yorkists made it back to London spreading news of a Lancastrian victory while Oxford’s men were busy looting the town. Oxford managed to restore discipline to his troops and led them back to the battlefield but in the mist there was total confusion. Not only had the Lancastrians failed to exploit this advantage but their left flank had also suffered under attack from Yorkist forces led by Richard, Duke of Gloucester and the battle lines had rotated ninety degrees. Consequently, on their return, Oxford’s men went straight into their allied forces commanded by John Neville and their emblems were confused for the other side. Given the frequent and sudden changes of loyalty (like his brother John Neville had switched sides) each thought the other was the enemy and began attacking each other. Cries of treachery rang through the Lancastrian lines and their ranks broke up. John Neville was slain and, sensing all was lost, Richard Neville tried to make his escape but, although Edward wanted him alive, he too was killed in the chaos.

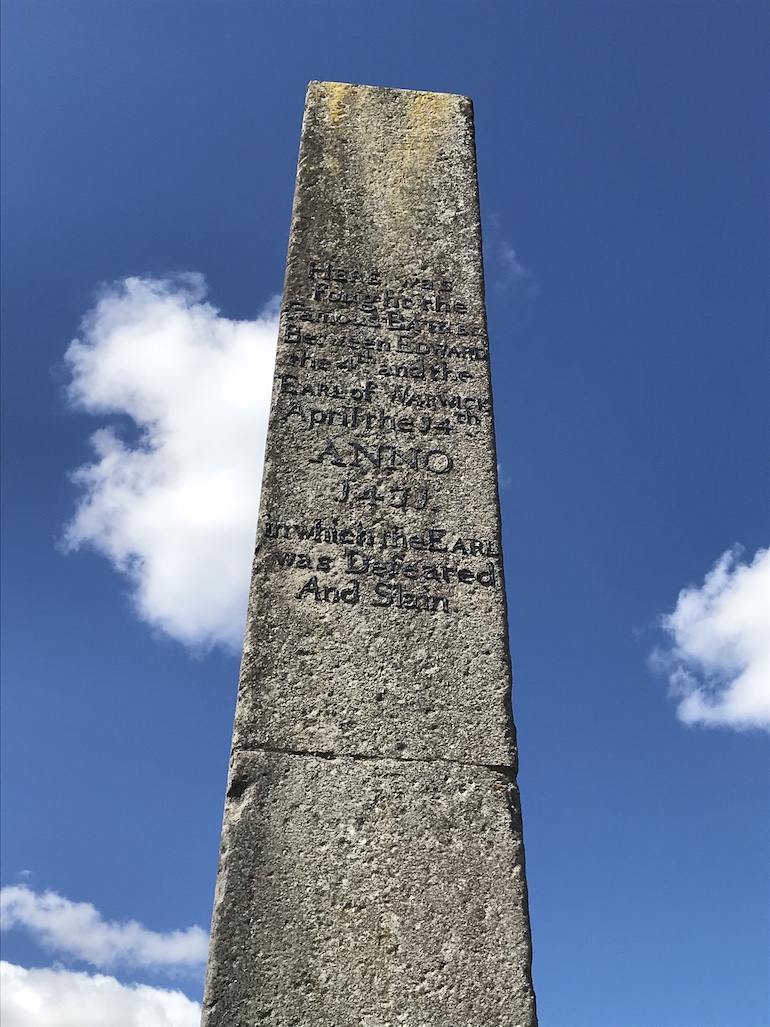

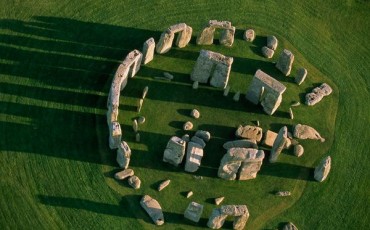

Today a stone pillar marks the spot whereby tradition Richard Neville was slain although the obelisk erected in 1740 was subsequently moved. The pillar itself is about 1 mile (1.6km) north of the town of Barnet but urbanisation has covered much of the battlefield. There is however an impressive model of the battlefield and displays regarding the battle at the Barnet Museum. The museum describes the battlefield as the only registered battlefield in greater London emphasising how despite its historical importance actual conflict was nearly always conducted away from the capital.

Battle of Barnet – 18th-century monument. Photo Credit: © Steven Szymanski.

Battle of Barnet – 18th-century monument. Photo Credit: © Steven Szymanski.

Leave a Reply